From Russia with Love (film)

| From Russia with Love | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Terence Young |

| Screenplay by | Richard Maibaum |

| Adaptation by | |

| Based on | From Russia, with Love by Ian Fleming |

| Produced by | Harry Saltzman Albert R. Broccoli |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ted Moore |

| Edited by | Peter R. Hunt |

| Music by | John Barry |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 115 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom[1] United States[2] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million |

| Box office | $79 million |

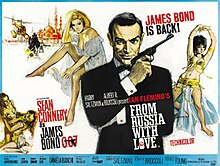

From Russia with Love is a 1963 spy film and the second in the James Bond series produced by Eon Productions, as well as Sean Connery's second role as MI6 agent 007 James Bond.

The picture was directed by Terence Young, produced by Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, and written by Richard Maibaum and Johanna Harwood, based on Ian Fleming's 1957 novel From Russia, with Love. In the film, Bond is sent to assist in the defection of Soviet consulate clerk Tatiana Romanova in Turkey, where SPECTRE plans to avenge Bond's killing of Dr. No. The film followed Dr. No (1962) and was followed by Goldfinger (1964).

Following the success of Dr. No, United Artists greenlit a sequel and doubled the budget available for the producers. In addition to filming on location in Turkey, the action scenes were shot at Pinewood Studios, Buckinghamshire, and in Scotland. Production ran over budget and schedule, and was rushed to finish by its scheduled October 1963 release date.

From Russia with Love was a critical and commercial success. It took in more than $78 million in worldwide box-office receipts, far more than its $2 million budget and more than its predecessor Dr. No, thereby becoming a blockbuster in 1960s cinema. The film is considered one of the best entries in the series. In 2004, Total Film magazine named it the ninth-greatest British film of all time; it was the only Bond film to appear on the list. It was also the first film in the series to win a BAFTA Award for Best Cinematography.

Plot

[edit]International criminal organisation SPECTRE seeks revenge against MI6 agent James Bond for the death of their agent Dr. No in Jamaica.[Notes 1] SPECTRE's chief planner, Czechoslovak chess grandmaster Kronsteen, devises a plan to lure Bond into a trap, using as bait the prospects of procuring a Lektor cryptography device from the Soviet Union's consulate in Istanbul. SPECTRE operative Rosa Klebb, a former head of SMERSH (Soviet counter-intelligence), is assigned to oversee the mission and chooses trained killer Donald Grant to assassinate Bond at the right moment. To set the trap, Klebb recruits a cipher clerk at the consulate, Tatiana Romanova, to unwittingly assist in the plan, tricking Romanova into believing Klebb is still working for SMERSH.

In London, Bond is called to a meeting with M and informed that Tatiana has requested Bond's help to defect to the West, in exchange for providing British intelligence with a Lektor. Exactly as Kronsteen predicted, M suspects a trap but decides to honour Tatiana's request. Before departing, Bond is equipped with a special briefcase from Q Branch, containing several defensive gadgets and an ArmaLite AR-7 sniper rifle, to help on his assignment. Upon arriving in Istanbul, Bond works alongside the head of MI6's branch in the city, Ali Kerim Bey, while he awaits word from Tatiana. Grant is shadowing Bond to protect him until he steals the Lektor. During this time, Kerim Bey is attacked by Soviet agent Krilencu. After an attack on the men while they hide out at a gypsy settlement, Kerim Bey assassinates Krilencu with Bond's help before he can flee the city.

Eventually, Tatiana meets Bond at his hotel suite, where she agrees to provide plans to the consulate to help him steal the Lektor. The pair spend the night together, unaware that Klebb and Grant are filming them. Upon receiving the consulate's floor plans and a description of the Lektor from Romanova, the latter which MI6 confirms, Bond and Kerim Bey make and execute a plan to steal the Lektor, before all three make haste to escape the city aboard the Orient Express. Aboard, Kerim Bey and Bond subdue Commissar Benz, a Soviet security officer. While Bond returns to Tatiana to wait for their rendezvous with one of Kerim Bey's sons, Grant kills both Kerim Bey and Benz. Angered, Bond questions Romanova's true motives.

When the train arrives in Belgrade, Bond informs one of Kerim Bey's sons of his father's death and receives instructions to rendezvous with a British agent named Nash at Zagreb. However, Grant overhears the conversation, kills Nash and assumes his identity. He drugs Tatiana at dinner and overpowers Bond. He reveals that Tatiana was a pawn in SPECTRE's plan; he intends to kill both her and Bond, staging it as a murder-suicide and leaving behind faked blackmail evidence which will scandalise the British intelligence community. Bond tricks Grant into setting off a booby trap in Bond's attache-case before the two engage in a fight and Bond kills Grant. Taking the Lektor and the film of their night together, Bond and Romanova leave the train in Istria, Yugoslavia and use Grant's escape plan. They evade helicopter and boat attacks by SPECTRE agents before reaching safety.

Learning of Grant's death and Bond's survival, SPECTRE's enigmatic chairman, Ernst Stavro Blofeld, has Kronsteen executed for his plan's disastrous failure. As the organisation promised to sell back the Lektor to the Russians, Klebb is ordered to recover it and kill Bond. Klebb reaches the pair, while they are resting in a hotel in Venice, and comes to their room disguised as a maid. Klebb orders Tatiana to leave the room while holding Bond at gunpoint. Tatiana then re-enters, tackling Klebb and knocking the pistol to the floor. Klebb and Bond struggle as Klebb attempts to stab Bond with a venom-tipped blade in one of her shoes. Tatiana picks up the pistol and kills Klebb. With their mission accomplished, Bond and Tatiana spend some time on a romantic boat ride.

Cast

[edit]- Sean Connery as James Bond, MI6 agent 007.

- Pedro Armendáriz as Ali Kerim Bey, head of MI6 Station T in Istanbul.

- Lotte Lenya as Rosa Klebb (SPECTRE No. 3), a former SMERSH colonel-turned-SPECTRE operative.

- Robert Shaw as Donald Grant, a cunning SPECTRE assassin and one of the principal Bond enemies.

- Bernard Lee as M, chief of British Intelligence.

- Daniela Bianchi as Tatiana Romanova, a Soviet Consulate clerk and Bond's love interest, based on Christine Granville.[3]

- Bianchi's dialogue was dubbed by an uncredited Barbara Jefford.[4]

- Eunice Gayson as Sylvia Trench, Bond's semi-regular girlfriend.

- Walter Gotell as Morzeny, a SPECTRE thug who trains personnel on SPECTRE Island.

- Francis de Wolff as Vavra, chief of a Gypsy tribe used for dirty work by Kerim Bey.

- George Pastell as a train conductor on the Orient Express.

- Nadja Regin as Kerim Bey's girl

- Lois Maxwell as Miss Moneypenny, M's secretary.

- Aliza Gur and Martine Beswick as Vida (in green) and Zora (in red), respectively, two jealous Gypsy girls who are disputing the same man.

- Vladek Sheybal as Kronsteen (SPECTRE No. 5), a Czechoslovak chess grandmaster and SPECTRE agent.

Credited as "?" in the film, Anthony Dawson portrayed Ernst Stavro Blofeld (SPECTRE No. 1), the head and mastermind of SPECTRE and Bond's nemesis. He had previously played Professor Dent in Dr. No. Dawson's dialogue was dubbed by an uncredited Eric Pohlmann[citation needed]. Fred Haggerty played Krilencu, a Bulgarian assassin who works as a killer for the Soviets in the Balkans. Desmond Llewelyn portrays Major Boothroyd, head of MI6 Q Branch and the equipment officer, making his first of many appearances that continued until 1999. Additional cast members include Neville Jason as Kerim Bey's chauffeur, Peter Bayliss as Russian agent Commissar Benz, Nusret Ataer as Mehmet, Kerim Bey's son, and Peter Madden as Canadian chessmaster McAdams. Uncredited performances include Michael Culver and Elizabeth Counsell as a couple in a punt, and William Hill as Captain Nash, a British agent killed and impersonated by Grant.[citation needed]

Production

[edit]Following the financial success of Dr. No, United Artists greenlit a second James Bond film. The studio doubled the budget offered to Eon Productions with $2 million, and also approved a bonus for Sean Connery, who would receive $100,000 along with his $54,000 salary.[5] As President John F. Kennedy had named Fleming's novel From Russia, with Love among his ten favourite books of all time in Life magazine,[6] producers Broccoli and Saltzman chose this as the follow-up to Bond's cinematic debut in Dr. No. The comma in the title of Fleming's novel was dropped for the film title. From Russia with Love was the last film President Kennedy saw at the White House on 20 November 1963 before going to Dallas.[7] Most of the crew from the first film returned, with major exceptions being production designer Ken Adam, who went to work on Dr. Strangelove and was replaced by Dr. No's uncredited art director Syd Cain. Title designer Maurice Binder was replaced by Robert Brownjohn. Stunt coordinator Bob Simmons was unavailable and was replaced by Peter Perkins[6] though Simmons performed stunts in the film.[8] John Barry replaced Monty Norman as composer of the soundtrack.

The film introduced several conventions which would become essential elements of the series: a pre-title sequence, the Blofeld character (referred to in the film only as "Number 1", though Blofeld is mentioned in the end credits, with the actor labeled as "?"), a secret-weapon gadget for Bond, a helicopter sequence (repeated in every subsequent Bond film except The Man with the Golden Gun), a postscript action scene after the main climax, a theme song with lyrics, and the line "James Bond will return/be back" in the credits.[9]

Writing

[edit]Ian Fleming's novel was a Cold War thriller but the producers replaced the Soviet undercover agency SMERSH with the crime syndicate SPECTRE so as to avoid controversial political overtones.[6] The SPECTRE training grounds were inspired by the film Spartacus.[10] The original screenwriter was Len Deighton, who accompanied Harry Saltzman, Syd Cain, and Terence Young to Istanbul,[11] but he was replaced because of a lack of progress.[12] Thus, two of Dr. No's writers, Johanna Harwood and Richard Maibaum, returned for the second film in the series.[6] Some sources state Harwood was credited for the "adaptation" mostly for her suggestions, which were carried over into Maibaum's script.[12] Harwood stated in an interview for Cinema Retro that she had been a screenwriter of several of Harry Saltzman's projects, and her screenplay for From Russia with Love had followed Fleming's novel closely, but she left the series due to what she called Terence Young's constant rewriting of her screenplay with ideas that were not in the original Fleming work.[13] Maibaum kept on making rewrites as filming progressed. Red Grant was added to the Istanbul scenes just prior to the film crew's trip to Turkey; this brought more focus to the SPECTRE plot, as Grant started saving Bond's life there (a late change during shooting involved Grant killing the bespectacled spy at Hagia Sophia instead of Bond, who ends up just finding the man dead).[6] For the last quarter of the movie, Maibaum added two chase scenes, with a helicopter and speedboats, and changed the location of Bond and Klebb's battle from Paris to Venice.[14] Uncredited rewrites were contributed by Berkely Mather.

Casting

[edit]Although uncredited, the actor who played Number 1 was Anthony Dawson, who had played Professor Dent in the previous Bond film, Dr. No, and appeared in several of Terence Young's films. In the end credits, Blofeld is credited with a question mark. Blofeld's lines were redubbed by Viennese actor Eric Pohlmann in the final cut.[6] Peter Burton was unavailable to return as Major Boothroyd, so Desmond Llewelyn, a Welsh actor who was a fan of the Bond comic strip published in the Daily Express, accepted the part. However, screen credit for Llewelyn was omitted at the opening of the film and is reserved for the exit credits, where he is credited simply as "Boothroyd". Llewelyn's character is not referred to by this name in dialogue, but M does introduce him as being from Q Branch. Llewelyn remained as the character, better known as Q, in all but one of the series' films until his death in 1999.[15][16]

Several actresses were considered for the role of Tatiana, including Italians Sylva Koscina and Virna Lisi, Danish actress Annette Vadim, Polish actress Magda Konopka, Swedish actress Pia Lindström, and English-born Tania Mallet.[17][18] Elga Gimba Andersson was nearly cast in the role but was fired after refusing to have sex with a United Artists executive.[18] 1960 Miss Universe runner-up Daniela Bianchi was ultimately cast, supposedly Sean Connery's choice. Bianchi started taking English classes for the role, but the producers ultimately chose to have her lines redubbed by British stage actress Barbara Jefford in the final cut.[19] The scene in which Bond finds Tatiana in his hotel bed was used for Bianchi's screen test, with Dawson standing in, this time, as Bond.[6] The scene later became the traditional screen test scene for prospective James Bond actors and Bond Girls.[20][21] In her initial scene with Klebb, Tatiana refers to training for the ballet, making a reference to the actress's background.

Greek actress Katina Paxinou was considered for the role of Rosa Klebb, but was unavailable. Terence Young cast Austrian singer Lotte Lenya after hearing one of her musical recordings. Young wanted Kronsteen's portrayer to be "an actor with a remarkable face", so the minor character would be well remembered by audiences. This led to the casting of Vladek Sheybal, whom Young also considered convincing as an intellectual.[10] Sheybal was initially hesitant to take the role but was convinced by Connery's girlfriend Diane Cilento.[18] Several women were tested for the roles of Vida and Zora, the two fighting Gypsy girls, and after Aliza Gur and Martine Beswick were cast, they spent six weeks practising their fight choreography with stunt work arranger Peter Perkins.[22] Beswick was mis-credited as 'Martin Beswick' in the film's opening titles, but this error was fixed for the 2001 DVD release.[23]

Mexican actor Pedro Armendáriz was recommended to Young by director John Ford to play Kerim Bey. After experiencing increasing discomfort on location in Istanbul, Armendáriz was diagnosed with inoperable cancer. Filming in Istanbul was terminated, the production moved to Britain, and Armendáriz's scenes were brought forward so that he could complete his scenes without delay. Though visibly in pain, he continued working as long as possible. When he could no longer work, he returned home and killed himself.[6] Remaining shots after Armendáriz left London had a stunt double and Terence Young himself as stand-ins.[4]

Englishman Joe Robinson was a strong contender for the role of Red Grant but it was given to Robert Shaw.[24]

Filming

[edit]Filming began on April 1, 1963, at Pinewood Studios.[6][18][25] Armendariz's scenes were shot first after he was diagnosed with terminal cancer, with Terence Young serving as a stand-in for Kerim Bey for the last two months of the production.[18] Most of the film was set in Istanbul, Turkey. Locations included the Basilica Cistern, Hagia Sophia and the Sirkeci railway station, which also was used for the Belgrade and Zagreb railway stations. The MI6 office in London, SPECTRE Island, the Venice hotel and the interior scenes of the Orient Express were filmed at Pinewood Studios with some footage of the train. In the film, the train journey was set in Eastern Europe. The journey and the truck ride were shot in Argyll, Scotland and Switzerland. The end scenes for the film were shot in Venice.[6] However, to qualify for the British film funding of the time, at least 70 per cent of the film had to have been filmed in Great Britain or the Commonwealth.[26] The Gypsy camp was also to be filmed in an actual camp in Topkapi, but was actually shot in a replica of it in Pinewood.[19] The scene with rats (after the theft of the Lektor) was shot in Spain, as Britain did not allow filming with wild rats, and an attempt to film white rats painted in cocoa in Turkey did not work.[27] Principal photography wrapped on 23 August.[28] Ian Fleming spent a week in the Istanbul shoot, supervising production and touring the city with the producers.[29][18]

Director Terence Young's eye for realism was evident throughout production. For the opening chess match, Kronsteen wins the game with a reenactment of Boris Spassky's victory over David Bronstein in 1960.[30] Production Designer Syd Cain built up the "chess pawn" motif in his $150,000 set for the brief sequence.[19] Cain also later added a promotion to another movie Eon was producing, making Krilencu's death happen inside a billboard for Call Me Bwana.[18] A noteworthy gadget featured was the attaché case (briefcase) issued by Q Branch. It had a tear gas bomb that detonated if the case was improperly opened, a folding AR-7 sniper rifle with twenty rounds of ammunition, a throwing knife, and 50 gold sovereigns. A boxer at Cambridge, Young choreographed the fight between Grant and Bond along with stunt coordinator Peter Perkins. The scene took three weeks to film and was violent enough to worry some on the production. Robert Shaw and Connery did most of the stunts themselves.[4][6] Young stated that the château garden assassination of the fake Bond in the pre-credits sequence is styled after Last Year at Marienbad.[31]

After the unexpected loss of Armendáriz, production proceeded, experiencing complications from uncredited rewrites by Berkely Mather during filming. Editor Peter Hunt set about editing the film while key elements were still to be filmed, helping to restructure the opening scenes. Hunt and Young came up with the idea of moving the Red Grant training sequence to the beginning of the film (prior to the main title), a signature feature that has been an enduring hallmark of every Bond film since. The briefing with Blofeld was rewritten, and back projection was used to refilm Lotte Lenya's lines.[6]

Behind schedule and over budget, the production crew struggled to complete production in time for the already-announced premiere date that October. On 6 July 1963, while scouting locations in Argyll, Scotland, for that day's filming of the climactic boat chase, Terence Young's helicopter crashed into the water with art director Michael White and a cameraman aboard. The craft sank into 40–50 feet (12–15 m) of water, but all escaped with minor injuries. Despite the calamity, Young was behind the camera for the full day's work. A few days later, Bianchi's driver fell asleep during the commute to a 6 am shoot and crashed the car. The actress's face was bruised and Bianchi's scenes had to be delayed for two weeks while the facial contusions healed.[6]

The helicopter and boat chase scenes were not in the original novel but were added to create an action climax. The former was inspired by the crop-dusting scene in Alfred Hitchcock's North by Northwest and the latter by a previous Young/Broccoli/Maibaum collaboration, The Red Beret.[32] These two scenes would initially be shot in Istanbul but were moved to Scotland. The speedboats could not go fast enough due to the many waves in the sea,[33] and a rented boat filled with cameras ended up sinking in the Bosphorus.[19] A helicopter was also hard to obtain, and the special effects crew were nearly arrested trying to get one at a local airbase.[33][34] The helicopter chase was filmed with a radio controlled miniature helicopter.[19] The sounds of the boat chase were replaced in post-production since the boats were not loud enough,[35] and the explosion, shot in Pinewood, got out of control, burning Walter Gotell's eyelids[33] and seriously injuring three stuntmen.[32]

Photographer David Hurn was commissioned by the producers of the James Bond films to shoot a series of stills with Sean Connery and the actresses of the film. When the prop Walther PPK pistol did not arrive, Hurn volunteered the use of his own Walther LP-53 air pistol.[36] Though the photographs of the "James Bond is Back" posters of the US release airbrushed out the long barrel of the pistol, film poster artist Renato Fratini used the long-barrelled pistol for his drawings of Connery on the British posters.[37]

For the opening credits, Maurice Binder had disagreements with the producers and did not want to return.[38] Designer Robert Brownjohn stepped into his place, and projected the credits on female dancers, inspired by constructivist artist László Moholy-Nagy projecting light onto clouds in the 1920s.[39] Brownjohn's work started the tradition of scantily clad women in the Bond films' title sequences.[40]

Music

[edit]From Russia with Love is the first Bond film in the series with John Barry as the primary soundtrack composer.[41] The theme song was composed by Lionel Bart of Oliver! fame and sung by Matt Monro,[42] although the title credit music is a lively instrumental version of the tune beginning with Barry's brief "James Bond Is Back" then segueing into Monty Norman's "James Bond Theme". Monro's vocal version is later played during the film (as source music on a radio) and properly over the film's end titles.[42] Barry travelled with the crew to Turkey to try getting influences of the local music, but ended up using almost nothing, just local instruments such as finger cymbals to give an exotic feeling, since he thought the Turkish music had a comedic tone that did not fit in the "dramatic feeling" of the James Bond movies.[43] Frank Sinatra was considered for singing the theme song, but Sinatra turned the part down.[44]

Recalling his visit to Istanbul, John Barry said, "It was like no place I'd ever been in my life. [The Trip] was supposedly to seep up the music, so Noel Rogers and I used to go 'round to these nightclubs and listen to all this stuff. We had the strangest week, and really came away with nothing, except a lot of ridiculous stories. We went back, talked to Lionel, and then he wrote 'From Russia with Love.'''[45]

In this film, Barry introduced the percussive theme "007"—action music that came to be considered the "secondary James Bond theme". He composed it to have a lighter, enthusiastic and more adventurous theme to relax the audience.[43] The arrangement appears twice on the soundtrack album; the second version, titled "007 Takes the Lektor", is the one used during the gunfight at the Gypsy camp and also during Bond's theft of the Lektor decoding machine.[6][46] The completed film features a holdover from the Monty Norman-supervised Dr. No music, as the post-rocket-launch music from Dr. No is played in From Russia with Love during the helicopter and speedboat attacks.[46]

Release and reception

[edit]From Russia with Love premiered on 10 October 1963 at the Odeon Leicester Square in London.[47] Ian Fleming, Sean Connery and Walter Gotell attended the premiere. The following year, it was released in 16 countries worldwide, with the United States premiere on 8 April 1964, at New York's Astor Theatre.[48] Upon its first release, From Russia with Love doubled Dr. No's gross by earning $12.5 million ($123 million in 2023 dollars[49]) at the worldwide box office.[50] After reissue it grossed $78 million,[51] of which $24 million was from North America.[52] It was the most popular movie at the British box office in 1963.[53]

The film's cinematographer Ted Moore won the BAFTA award and the British Society of Cinematographers award for Best Cinematography.[54] At the 1965 Laurel Awards, Lotte Lenya stood third for Best Female Supporting Performance, and the film secured second place in the Action-Drama category. The film was also nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song for "From Russia with Love".[55]

Contemporary reviews

[edit]In comparing the film to its predecessor, Dr. No, Richard Roud, writing in The Guardian, wrote that From Russia with Love "didn't seem quite so lively, quite so fresh, or quite so rhythmically fast-moving."[56] He went on to say that "... the film is highly immoral in every imaginable way; it is neither uplifting, instructive nor life-enhancing. Neither is it great film-making. But it sure is fun."[56] Writing in The Observer, Penelope Gilliatt noted that "The way the credits are done has the same self-mocking flamboyance as everything else in the picture."[57] Gilliatt went on to say that the film manages "to keep up its own cracking pace, nearly all the way. The set-pieces are a stunning box of tricks".[57] The critic for The Times wrote of Bond that he is "the secret ideal of the congenital square, conventional in every particular ... except in morality, where he has the courage—and the physical equipment—to do without thinking what most of us feel we might be doing ..."[58] The critic thought that overall, "the nonsense is all very amiable and tongue-in-cheek and will no doubt make a fortune for its devisers".[58]

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote: "Don't miss it! This is to say, don't miss it if you can still get the least bit of fun out of lurid adventure fiction and pseudo-realistic fantasy. For this mad melodramatization of a desperate adventure of Bond with sinister characters in Istanbul and on the Orient Express is fictional exaggeration on a grand scale and in a dashing style, thoroughly illogical and improbable, but with tongue blithely wedged in cheek."[59] Time magazine called the film "fast, smart, shrewdly directed and capably performed."[60] Variety described the film as "a preposterous, skillful slab of hardhitting, sexy hokum. After a slowish start, it is directed by Terence Young at zingy pace. The cast perform with an amusing combo of tongue-in-cheek and seriousness and the Istanbul location is an added bonus."[61]

Later reviews

[edit]From Russia with Love received critical praise from critics decades following the film's original release and is considered one of the finest Bond films. Rotten Tomatoes sampled 62 reviewers and judged 97% of the reviews to be positive with an average rating of 7.9/10. Its summary states: "The second James Bond film, From Russia with Love, is a razor-sharp, briskly-paced Cold War thriller that features several electrifying action scenes."[62]

In his 1986 book Guide for the Film Fanatic, Danny Peary described From Russia with Love as "an excellent, surprisingly tough and gritty James Bond film" which is "refreshingly free of the gimmickry that would characterise the later Bond films, and Connery and Bianchi play real people. We worry about them and hope their relationship will work out ... Shaw and Lotte Lenya are splendid villains. Both have exciting, well-choreographed fights with Connery. Actors play it straight, with excellent results."[63]

Film critic James Berardinelli cited this as his favourite Bond film, writing "Only From Russia with Love avoids slipping into the comic book realm of Goldfinger and its successors while giving us a sampling of the familiar Bond formula (action, gadgets, women, cars, etc.). From Russia with Love is effectively paced and plotted, features a gallery of detestable rogues (including the ultimate Bond villain, Blofeld), and offers countless thrills".[64]

In June 2001 Neil Smith of BBC Films called it "a film that only gets better with age".[65] In 2004, Total Film magazine named it the ninth-greatest British film of all time, making it the only James Bond film to appear on the list.[66] In 2006, Jay Antani of Filmcritic praised the film's "impressive staging of action scenes",[67] while IGN listed it as second-best Bond film ever, behind only Goldfinger.[68] That same year, Entertainment Weekly put the film at ninth among Bond films, criticising the slow pace.[69] When the "James Bond Ultimate Collector's Set" was released in November 2007 by MGM, Norman Wilner of MSN chose From Russia with Love as the best Bond film.[70] Conversely, in his book about the Bond phenomenon, The Man With the Golden Touch, British author Sinclair McKay states "I know it is heresy to say so, and that some enthusiasts regard From Russia With Love as the Holy Grail of Bond, but let's be searingly honest – some of it is crashingly dull."[71] In 2014 Time Out polled several film critics, directors, actors and stunt actors to list their top action films;[72] From Russia With Love was listed at 69.[73]

The British Film Institute's screenonline guide called the film "one of the series' high points" and said it "had advantages not enjoyed by many later Bond films, notably an intelligent script that retained the substance of Ian Fleming's novel while toning down the overt Cold War politics (the Cuban Missile Crisis had only occurred the previous year)."[74] In 2008, Michael G. Wilson, the current co-producer of the series, stated "We always start out trying to make another From Russia with Love and end up with another Thunderball."[75] Sean Connery,[4] Michael G. Wilson, Barbara Broccoli, Timothy Dalton and Daniel Craig also consider this their favourite Bond film.[76][failed verification] Albert Broccoli listed it with Goldfinger and The Spy Who Loved Me as one of his top three favourites,[77] explaining that he felt "it was with this film that the Bond style and formula were perfected".[78]

Video game adaptation

[edit]In 2005, the From Russia with Love video game was developed by Electronic Arts and released on 1 November 2005 in North America. It follows the storyline of the book and film, albeit adding in new scenes, making it more action-oriented. One of the most significant changes to the story is the replacement of the organisation SPECTRE to OCTOPUS because the name SPECTRE constituted a long-running legal dispute over the film rights to Thunderball between United Artists/MGM and writer Kevin McClory. Most of the cast from the film returned in likeness. Connery not only allowed his 1960s likeness as Bond to be used, but the actor, in his 70s, also recorded the character's dialogue, marking a return to the role 22 years after he last played Bond in Never Say Never Again. Featuring a third-person multiplayer deathmatch mode, the game depicts several elements of later Bond films, such as the Aston Martin DB5 from Goldfinger (1964) and the rocket belt from Thunderball (1965).[79][80]

The game was written by Bruce Feirstein, who had previously worked on the film scripts for GoldenEye, Tomorrow Never Dies, The World Is Not Enough, and the 2004 video game Everything or Nothing. Its soundtrack was composed by Christopher Lennertz and Vic Flick.[81]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "From Russia with Love". Lumiere. European Audiovisual Observatory. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ From Russia with Love, AFI Catalog American Film Institute. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ FILMFAX Magazine. October 2003 – January 2004.

- ^ a b c d From Russia with Love Ultimate Edition DVD (Media notes). Terence Young. MGM Home Entertainment. 2006 [1962]. Accessed 30 December 2007.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Balio, Tino (1987). United Artists: the company that changed the film industry. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 260. ISBN 9780299230135.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Martine Beswick, Daniela Bianchi, Dana Broccoli, Syd Cain, Sean Connery, Peter Hunt, John Stears, Norman Wanstall (2000). Inside From Russia with Love (DVD). MGM Home Entertainment Inc. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ "Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., 1917–2007". The American Prospect. 17 September 2010. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ Brosnan, John James Bond in the Cinema Tantivy Press; 2nd edition (1981)

- ^ "James Bond Retrospective: From Russia With Love (1963)". Whatculture. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ a b Terence Young. From Russia with Love audio commentary. MGM Home Entertainment. Accessed 17 October 2008. From Russia with Love Ultimate Edition, Disc 1

- ^ "Len Deighton on From Russia With Love | The Spy Command". Hmssweblog.wordpress.com. 5 November 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ a b McGilligan, Patrick (1986). Backstory: interviews with screenwriters of Hollywood's golden age. University of California Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-520-05689-3.

- ^ Johanna Harwood Interview Movie Classics # 4 Solo Publishing 2012

- ^ Chapman, James (2007). Licence to Thrill. London/New York City: Cinema and Society. ISBN 978-1-84511-515-9.

- ^ Simpson, Paul (2002). The rough guide to James Bond. Rough Guides. p. 83. ISBN 9781843531425. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Inside Q's Lab". On Her Majesty's Secret Service Ultimate Edition (DVD). MGM/UA Home Entertainment Inc.

- ^ Inside From Russia with Love (DVD). MGM/UA Home Entertainment Inc. 2000.

- ^ a b c d e f g Field, Matthew (2015). Some kind of hero : 007 : the remarkable story of the James Bond films. Ajay Chowdhury. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-6421-0. OCLC 930556527.

- ^ a b c d e From Russia with Love audio commentary, Ultimate Edition DVD

- ^ Inside Octopussy (DVD). MGM Home Entertainment Inc. 2000. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ Inside The Living Daylights (DVD). MGM Home Entertainment Inc. 2000. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ Aliza Gur. From Russia with Love audio commentary. MGM Home Entertainment. Accessed 20 October 2008. From Russia with Love Ultimate Edition, Disc 1

- ^ "From Russia with Love". www.007museum.com.

- ^ "Joe has eye of the Tiger". The Visitor. 10 August 2004. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ Coincidentally, this was also the date of first publication of the Bond novel On Her Majesty's Secret Service

- ^ Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcu (1997). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. Batsford Books. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

- ^ Syd Cain. From Russia with Love audio commentary. MGM Home Entertainment. Accessed 20 October 2008. From Russia with Love Ultimate Edition, Disc 1

- ^ Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcu (1997). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. Batsford Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

- ^ Lycett, Andrew (1996). Ian Fleming. London: Phoenix. p. 418. ISBN 978-1-85799-783-5.

- ^ "The name is Spassky – Boris Spassky". ChessBase.com. 2 September 2004. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ^ Rubin, Steven Jay (1981). The James Bond Films: A Behind the Scenes History. Westport, Connecticut: Arlington House. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-87000-524-4.

- ^ a b John Cork. From Russia with Love audio commentary. MGM Home Entertainment. Accessed 20 October 2008. From Russia with Love Ultimate Edition, Disc 1

- ^ a b c Walter Gotell. From Russia with Love audio commentary. MGM Home Entertainment. Accessed 17 October 2008. From Russia with Love Ultimate Edition, Disc 1

- ^ John Stears. From Russia with Love audio commentary. MGM Home Entertainment. Accessed 17 October 2008. From Russia with Love Ultimate Edition, Disc 1

- ^ Norman Wanstall. From Russia with Love audio commentary. MGM Home Entertainment. Accessed 20 October 2008. From Russia with Love Ultimate Edition, Disc 1

- ^ "From Russia With Love, 1963". Christie's. 14 February 2001. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Poster Galore". British Film Institute. 10 January 2007. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ Starlog magazine Maurice Binder interview Part 1

- ^ "Robert Brownjohn / 15 October 2005 to 26 February 2006 : – Design/Designer Information". Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-08.

- ^ Jütting, Kerstin (2007). "Grow Up, 007!" – James Bond Over the Decades: Formula Vs. Innovation. GRIN Verlag. p. 13. ISBN 978-3-638-85372-9.

- ^ ""From Russia with Love" (1963) at Soundtrack Incomplete". Loki Carbis. Archived from the original on 16 August 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ a b "Listology: Rating the James Bond Theme Songs". Listology.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2006. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ a b John Barry. From Russia with Love audio commentary. MGM Home Entertainment. From Russia with Love Ultimate Edition, Disc 1

- ^ "Desde Rusia con amor | Música". 9 July 2008.

- ^ Burlingame, Jon (1 November 2012). The Music of James Bond. Oxford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780199986767.

- ^ a b The Music of James Bond (DVD). MGM Home Entertainment Inc. 2000. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ "A Premium for Bond-Lovers:"From Russia with Love"". The Illustrated London News. London. 5 October 1963. p. 527.

- ^ Sellers, Robert (1999). Sean Connery: a celebration. Robert Hale. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7090-6125-0.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Balio, Tino (2009). United Artists, Volume 2, 1951–1978: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-299-23014-2.

The picture grossed twice as much as Dr. No, both foreign and domestic – $12.5 million worldwide

- ^ "From Russia with Love". The Numbers. Nash Information Service. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ "From Russia, with Love (1964)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "Most Popular Films of 1963". The Times. London. 3 January 1964. p. 4.

- ^ "Awards at Yahoo Movies". Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- ^ "Awards won by From Russia with Love". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ a b Roud, Richard (11 October 1963). "New Films". The Guardian. London. p. 11.

- ^ a b Gilliatt, Penelope (13 October 1963). "Laughing it off with Bond: Films". The Observer. London. p. 27.

- ^ a b "Four Just Men Rolled into One". The Times. London. 10 October 1963. p. 17.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (9 April 1964). "James Bond Travels the Orient Express". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ^ "Cinema: Once More Unto the Breach". Time. 10 April 1964. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ^ "Film Reviews: From Russia with Love". Variety. 16 October 1963. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "From Russia With Love (1963)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Danny Peary, Guide for the Film Fanatic (Simon & Schuster, 1986) p.163

- ^ Berardinelli, James. "Top 100 Runner Up: From Russia with Love". Reelviews. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ "From Russia with Love (1963)". BBC. 19 June 2001. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ "Get Carter tops British film poll". BBC News. 3 October 2004. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ Antani, Jay. "From Russia with Love". Filmcritic.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ "James Bond's Top 20". IGN. 17 November 2006. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ^ Benjamin Svetkey, Joshua Rich (15 November 2006). "Ranking the Bond Films". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ Norman Wilner. "Rating the Spy Game". MSN. Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ^ McKay, Sinclair. The Man With the Golden Touch. Overlook Press: New York. 2008. Pg. 4

- ^ "The 100 best action movies". Time Out. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "The 100 best action movies: 70–61". Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

- ^ Michael Brooke. "From Russia With Love (1963)". screenonline. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ^ Nusair, David (1 November 2008). "From Russia With Love". AskMen. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ Fischer, Paul (2008). "Broccoli and Wilson Rejuvenate Bond Franchise". FilmMonthly. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ COLIN M JARMAN (27 June 2010). "IN MEMORY: Albert 'Cubby' Broccoli – The Mastermind behind the James Bond movies". Licensetoquote.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ Chapman, James (2007). Licence to thrill: a cultural history of the James Bond films. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-515-9.

- ^ "Interview with David Carson". GameSpy. 29 September 2005. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ Navarro, Alex (1 November 2005). "From Russia With Love Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 24 March 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ Electronic Arts (1 November 2005). From Russia with Love.

Bibliography

- Peary, Danny (1991). Cult Movie Stars. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-74924-8.

- Rubin, Steven Jay (2003). The Complete James Bond Movie Encyclopedia. New York: Contemporary Books. ISBN 978-0-07-141246-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Erickson, Glenn (22 July 2006). "Jump Cut 3: The British Censorship of From Russia with Love from research by Gavin Salkeld". DVDTalk.com. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- Tibbetts, John C., and James M. Welsh, eds. The Encyclopedia of Novels Into Film (2nd ed. 2005) pp 146–147.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- From Russia with Love at the BFI's Screenonline

- From Russia with Love at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- From Russia with Love at IMDb

- From Russia with Love at the TCM Movie Database

- From Russia with Love at AllMovie

- From Russia with Love at Rotten Tomatoes

- From Russia with Love at Box Office Mojo

- 1963 films

- 1960s action films

- 1960s American films

- 1960s British films

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s spy films

- 1960s thriller films

- American sequel films

- American spy films

- British sequel films

- British spy films

- Cold War spy films

- Defection in fiction

- Eon Productions films

- Films about Romani people

- Films directed by Terence Young

- Films produced by Albert R. Broccoli

- Films produced by Harry Saltzman

- Films scored by John Barry (composer)

- Films scored by Monty Norman

- Films set in Belgrade

- Films set in Istanbul

- Films set in London

- Films set in Turkey

- Films set in Venice

- Films set in Yugoslavia

- Films set in Zagreb

- Films set on the Orient Express

- Films set on trains

- Films shot at Pinewood Studios

- Films shot in Argyll and Bute

- Films shot in Berkshire

- Films shot in Buckinghamshire

- Films shot in Gwynedd

- Films shot in Istanbul

- Films shot in Madrid

- Films shot in Scotland

- Films shot in Switzerland

- Films shot in Venice

- Films shot in Wales

- Films with screenplays by Berkely Mather

- Films with screenplays by Johanna Harwood

- Films with screenplays by Richard Maibaum

- From Russia with Love (film)

- James Bond films

- United Artists films

- English-language action adventure films

- English-language thriller films