Russian Civil War

| Russian Civil War | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russian Revolution, revolutions of 1917–1923, and the aftermath of World War I | ||||||||||

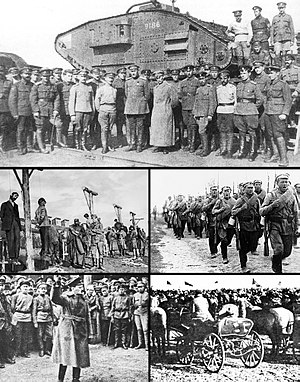

Clockwise from top left:

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

Bolsheviks:

| White movement: | Separatists: | ||||||||

| Anti-Bolshevik left: | Allied intervention: | Central Powers: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

| Strength | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||||

|

|

| |||||||||

| ||||||||||

The Russian Civil War (Russian: Гражданская война в России, romanized: Grazhdanskaya voyna v Rossii) was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the overthrowing of the liberal-democratic Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. It resulted in the formation of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and later the Soviet Union in most of its territory. Its finale marked the end of the Russian Revolution, which was one of the key events of the 20th century.

The Russian monarchy ended with the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II during the February Revolution, and Russia was in a state of political flux. A tense summer culminated in the October Revolution, where the Bolsheviks overthrew the provisional government of the new Russian Republic. Bolshevik seizure of power was not universally accepted, and the country descended into civil war. The two largest combatants were the Red Army, fighting for the establishment of a Bolshevik-led socialist state headed by Vladimir Lenin, and the forces known as the White movement (and its White Army), led mainly by the right-leaning officers of the Russian Empire, united around the figure of Alexander Kolchak. In addition, rival militant socialists, notably the Ukrainian anarchists of the Makhnovshchina and Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, were involved in conflict against the Bolsheviks. They, as well as non-ideological green armies, opposed the Bolsheviks, the Whites and the foreign interventionists.[12] Thirteen foreign states intervened against the Red Army, notably the Allied intervention, whose primary goal was re-establishing the Eastern Front of World War I. Three foreign states of the Central Powers also intervened, rivaling the Allied intervention with the main goal of retaining the territory they had received in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Soviet Russia.

The Bolsheviks initially consolidated control over most of the former empire. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was an emergency peace with the German Empire, who had captured vast swathes of the Russian territory during the chaos of the revolution. In May 1918, the Czechoslovak Legion in Russia revolted in Siberia. In reaction, the Allies began their North Russian and Siberian interventions. That, combined with the creation of the Provisional All-Russian Government, saw the reduction of Bolshevik-controlled territory to most of European Russia and parts of Central Asia. In 1919, the White Army launched several offensives from the east in March, the south in July, and west in October. The advances were later checked by the Eastern Front counteroffensive, the Southern Front counteroffensive, and the defeat of the Northwestern Army.

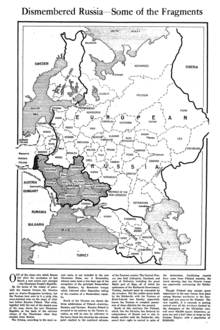

By 1919, the White armies were in retreat and by the start of 1920 were defeated on all three fronts.[13] Although the Bolsheviks were victorious, the territorial extent of the Russian state had been reduced, for many non-Russian ethnic groups had used the disarray to push for national independence.[14] In March 1921, during a related war against Poland, the Peace of Riga was signed, splitting disputed territories in Belarus and Ukraine between the Republic of Poland on one side and Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine on the other. Soviet Russia invaded all the newly independent nations of the former empire or supported the Bolshevik and socialist forces there, although the success of such invasions was limited. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania all repelled Soviet invasions, while Ukraine, Belarus (as a result of the Polish–Soviet War), Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia were occupied by the Red Army.[15][16] By 1921, the Bolsheviks had defeated the national movements in Ukraine and the Caucasus, although anti-Bolshevik uprisings in Central Asia lasted until the late 1920s.[17]

The armies under Kolchak were eventually forced on a mass retreat eastward. Bolshevik forces advanced east, despite encountering resistance in Chita, Yakut and Mongolia. Soon the Red Army split the Don and Volunteer armies, forcing evacuations in Novorossiysk in March and Crimea in November 1920. After that, fighting was sporadic until the war ended with the capture of Vladivostok in October 1922, but anti-Bolshevik resistance continued with the Muslim Basmachi movement in Central Asia and Khabarovsk Krai until 1934. There were an estimated 7 to 12 million casualties during the war, mostly civilians.[18]

Background

From World War I to the Russian Revolution

The Russian Empire fought in World War I from 1914 alongside France and the United Kingdom (Triple Entente) against Germany, Austria-Hungary and Ottoman Empire (Central Powers).

The February Revolution of 1917 resulted in the abdication of Emperor Nicholas II of Russia. As a result, the social-democratic Russian Provisional Government was established, and soviets, elected councils of workers, soldiers, and peasants, were organized throughout the country, leading to a situation of dual power. The Russian Republic was proclaimed in September of the same year.

October Revolution

The Provisional Government, led by Socialist Revolutionary Party politician Alexander Kerensky, was unable to solve the most pressing issues of the country, most importantly to end the war with the Central Powers. A failed military coup by General Lavr Kornilov in September 1917 led to a surge in support for the Bolsheviks, who took control of the soviets, which until then had been controlled by the Socialist Revolutionaries. Promising an end to the war and "all power to the Soviets", the Bolsheviks then ended dual power by overthrowing the Provisional Government in late October, on the eve of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, in what would be the second Revolution of 1917. The initial stage of the October Revolution which involved the assault on Petrograd occurred largely without any human casualties.[19][20][21] Despite the Bolsheviks' seizure of power, they lost to the Socialist Revolutionary Party in the 1917 Russian Constituent Assembly election, and the Constituent Assembly was dissolved by the Bolsheviks in retaliation. The Bolsheviks soon lost the support of other far-left allies, such as the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, after their acceptance of the terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk presented by the German Empire.[22] Conversely, a number of prominent members of the Left Socialist Revolutionaries had assumed positions in Lenin's government and led commissariats in several areas. This included agriculture (Kolegaev), property (Karelin), justice (Steinberg), post offices and telegraphs (Proshian) and local government (Trutovsky).[23] The Bolsheviks also reserved a number of vacant seats in the Soviets and Central Executive for the Menshevik and Left Socialist Revolutionaries parties in proportion to their vote share at the Congress.[24] The dissolution of the Constituent Assembly was also approved by the Left Socialist Revolutionaries and anarchists, both groups were in favour of a more radical democracy.[25]

Formation of the Red Army

From mid-1917 onwards, the Russian Army, the successor-organisation of the old Imperial Russian Army, started to disintegrate;[26] the Bolsheviks used the volunteer-based Red Guards as their main military force, augmented by an armed military component of the Cheka (the Bolshevik state secret police). In January 1918, after significant Bolshevik reverses in combat, the future Russian People's Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs Leon Trotsky headed the reorganization of the Red Guards into a Workers' and Peasants' Red Army in order to create a more effective fighting force. The Bolsheviks appointed political commissars to each unit of the Red Army to maintain morale and to ensure loyalty.

In June 1918, when it had become apparent that a revolutionary army composed solely of workers would not suffice, Trotsky instituted mandatory conscription of the rural peasantry into the Red Army.[27] The Bolsheviks overcame opposition of rural Russians to Red Army conscription units by taking hostages and shooting them when necessary in order to force compliance.[28] The forced conscription drive had mixed results, successfully creating a larger army than the Whites, but with members indifferent towards communist ideology.[22]

The Red Army also utilized former Tsarist officers as "military specialists" (voenspetsy);[29] sometimes their families were taken hostage in order to ensure their loyalty.[30] At the start of the civil war, former Tsarist officers formed three-quarters of the Red Army officer-corps.[30] By its end, 83% of all Red Army divisional and corps commanders were ex-Tsarist soldiers.[29]

Constituent Assembly opposition

Dissolution of the Constituent Assembly, early Constituent Assembly rebellions

The Russian Constituent Assembly had been a demand of the Bolsheviks against the Provisional Government, which kept delaying it. After the October Revolution the elections were run by the body appointed by the previous Provisional Government. It was based on universal suffrage but used party lists from before the Left-Right SR split. The anti-Bolshevik Right SRs won the elections with the majority of the seats,[31] after which Lenin's Theses on the Constituent Assembly argued in Pravda that formal democracy was impossible because of class conflicts, conflicts with Ukraine and the Kadet-Kaledin uprising. He argued the Constituent Assembly must unconditionally accept sovereignty of the soviet government or it would be dealt with "by revolutionary means".[32]

On December 30, 1917, the SR Nikolai Avksentiev and some followers were arrested for organizing a conspiracy. This was the first time Bolsheviks used this kind of repression against a socialist party. Izvestia said the arrest was not related to his membership in the Constituent Assembly.[33]

On January 4, 1918, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee made a resolution saying the slogan "all power to the constituent assembly" was counterrevolutionary and equivalent to "down with the soviets".[34]

The Constituent Assembly met on January 18, 1918. The Right SR Chernov was elected president defeating the Bolshevik supported candidate, the Left SR Maria Spiridonova (she would later break with the Bolsheviks and after the decades of gulag, she was shot on Stalin's orders in 1941). The Bolsheviks subsequently disbanded the Constituent Assembly and proceeded to rule the country as a one-party state with all opposition parties outlawed in 1921.[35][36] A simultaneous demonstration in favor of the Constituent Assembly was dispersed with force, but there was little protest afterwards.[37]

The first large Cheka repression involving the killing of libertarian socialists in Petrograd began in April 1918. On May 1, 1918, a pitched battle took place in Moscow between the anarchists and the Bolshevik police.[38]

Constituent Assembly uprising

The Union of Regeneration was founded in Moscow in April 1918 as an underground organization of "democratic resistance" to the Bolsheviks, composed of the Popular Socialists and "personal representatives" of Right Socialist Revolutionaries, Kadets and Defensists, among others. They were tasked with propping up anti-Bolshevik forces and to create a Russian state system based on "state consciousness, patriotism and civil liberties" with the goal to liberate the country from the "Germano-Bolshevik" yoke.[39][40][41]

On May 7, 1918, the Eighth Party Council of the Socialist Revolutionary Party commenced in Moscow and recognized the Union's leading role, putting aside political ideology and class for the purpose of Russia's salvation. They decided to start an uprising against the Bolsheviks with the goal of reconvening the Russian Constituent Assembly.[39] While preparations were under way, the Czechoslovak Legions overthrew Bolshevik rule in Siberia, the Urals and the Volga region in late May-early June 1918 and the center of SR activity shifted there. On June 8, 1918, five Constituent Assembly members formed the All-Russian Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly (Komuch) in Samara and declared it the new supreme authority in the country.[42] The Social Revolutionary Provisional Government of Autonomous Siberia came to power on 29 June 1918, after the uprising in Vladivostok.

White movement and foreign interventions

From "democratic counter-revolution" to the White movement

The main Russian military and political force opposing the Bolsheviks was known as the White movement, or simply the Whites; its armed formations were known as the White Army.

Some historians distinguish the White movement from the so-called "democratic counter-revolution"[43][44] led mainly by the Right SRs and the Mensheviks that adhered to the values of parliamentary democracy and maintained anti-Bolshevik counter-governments (Komuch, Ufa Directory) on the basis with alliance with the right-wing parties of Russia until November 1918. Until this period, parliamentary democracy was the main tendency of the anti-Bolshevik forces on the East (but not the South) of Russia, but since then, the White movement unified on an authoritarian-right platform around the figure of Alexander Kolchak who rose to power through a military coup as its principal leader and his All-Russian government.[44][45][46] After the Kolchak coup, the Right SRs and the Mensheviks went to opposition to the Whites and co-operated with both factions of the Civil War on a tactical level, while also attempting to overthrow White administrations or establish themselves as "the third force" of the war: for example, they attempted to stage an anti-Kolchak mutiny in November 1919 with the help of the Czech general Radola Gajda, and in 1920, they formed an organisation called 'Political Centre' and successfully overthrew the White administration in Irkutsk.[47]

Although the White movement included a variety of political opinions, from the liberals through monarchists to the ultra-nationalist Black Hundreds,[48] and did not have universally-accepted leader or doctrine, the main force behind the movement were the conservative officers, and the resulting movement shared many traits with widespread right-wing counter-revolutionary movements of the time, namely nationalism, racism, distrust of liberal and democratic politics, clericalism, contempt for the common man and dislike of industrial civilization;[49] although not all of the participants of the movement wanted a restoration of Tsarism, it generally preferred it to the revolution, and its main goal became to establish an order which would share the main features of the imperial one;[46][50] its positive program was largely summarized in the slogan of "united and indivisible Russia" which meant the restoration of imperial state borders (excluding Poland and Finland)[51][52][53] and its denial of the right to self-determination and the resulting hostility towards the movements for national independence;[45] the movement is associated with pogroms and antisemitism, although its relations with the Jews were more complex, as at first, for example, Jewish properitors supported the anti-Bolsheviks, but later the movement became known for its antisemic pogroms and discrimanation against the Jews.[54]

When the White Army was created, the structure of the Russian Army of the Provisional Government period was used, while almost every individual formation had its own characteristics. The military art of the White Army was based on the experience of World War I, which, however, left a strong imprint on the specifics of the Civil War.[55]

Allied intervention

The Western Allies armed and supported the Whites. They were worried about a possible Russo-German alliance, the prospect of the Bolsheviks making good on their threats to default on Imperial Russia's massive foreign debts and the possibility that Communist revolutionary ideas would spread (a concern shared by many Central Powers). Hence, many of the countries expressed their support for the Whites, including the provision of troops and supplies. Winston Churchill declared that Bolshevism must be "strangled in its cradle".[56] The British and French had supported Russia during World War I on a massive scale with war materials.

After the treaty, it looked like much of that material would fall into the hands of the Germans. To meet that danger, the Allies intervened with Great Britain and France sending troops into Russian ports. There were violent clashes with the Bolsheviks. Britain intervened in support of the White forces to defeat the Bolsheviks and prevent the spread of communism across Europe.[57]

Central Powers anti-Bolshevik intervention

The Central Powers also supported the anti-Bolshevik forces and the whites; after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the main goals of the intervention were to maintain the newly conquered territories and prevent a re-establishment of the Eastern Front. After the defeat of the Central Powers, many armies that stayed mostly helped the Russian White Guard eradicate communists in the Baltics until their eventual withdrawal and defeat. Pro-German factions fought against the newly independent Baltic states until their defeat by the Baltic States, backed by the victorious Allies.

Pro-independence movements and German protectorates

The German Empire created several short-lived buffer states within its sphere of influence after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk: the United Baltic Duchy, Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, Kingdom of Lithuania, Kingdom of Poland,[58] the Belarusian People's Republic, and the Ukrainian State. Following Germany's Armistice in World War I in November 1918, the states were abolished.[59][60]

Finland was the first republic that declared its independence from Russia in December 1917 and established itself in the ensuing Finnish Civil War between nationalist German-supported White Guards and socialist Bolshevik-supported Red Guards from January–May 1918.[61] The Second Polish Republic, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia formed their own armies immediately after the abolition of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty and the start of the Soviet westward offensive and subsequent Polish-Soviet War in November 1918.[62]

Opposition and repression in Soviet Russia

Exclusion of Mensheviks and SRs

At the Fifth All–Russian Congress of Soviets of July 4, 1918, the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries had 352 delegates compared to 745 Bolsheviks out of 1132 total. The Left SRs raised disagreements on the suppression of rival parties, the death penalty, and mainly, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The Bolsheviks excluded the Right SRs and Mensheviks from the government on 14 June for associating with counterrevolutionaries and seeking to "organize armed attacks against the workers and peasants" (though Mensheviks did not exist as a united movement and were split into the left-wing "internationalist" and more right-wing factions), while the Left SRs advocated forming a government of all socialist parties. The Left SRs agreed with extrajudicial execution of political opponents to stop the counterrevolution, but opposed having the government legally pronouncing death sentences, an unusual position that is best understood within the context of the group's terrorist past. The Left SRs strongly opposed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and opposed Trotsky's insistence that no one try to attack German troops in Ukraine.[63]

According to historian Marcel Liebman, Lenin's wartime measures such as banning opposition parties was prompted by the fact that several political parties either took up arms against the new Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, or participated in sabotage, collaboration with the deposed Tsarists, or made assassination attempts against Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders.[64] Liebman noted that opposition parties such as the Cadets and Mensheviks who were democratically elected to the Soviets in some areas, then proceeded to use their mandate to welcome in Tsarist and foreign capitalist military forces.[64] In one incident in Baku, the British military, once invited in, proceeded to execute members of the Bolshevik Party who had peacefully stood down from the Soviet when they failed to win the elections. As a result, the Bolsheviks banned each opposition party when it turned against the Soviet government. In some cases, bans were lifted. This banning of parties did not have the same repressive character as later bans enforced under the Stalinist regime.[64]

Repression

In December 1917, Felix Dzerzhinsky was appointed to the duty of rooting out counter-revolutionary threats to the Soviet government. He was the director of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission (aka Cheka), a predecessor of the KGB that served as the secret police for the Soviets.[65]

The Bolsheviks had begun to see the anarchists as a legitimate threat and associate criminality such as robberies, expropriations and murders with anarchist associations. Subsequently, the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom) decided to liquidate criminal recklessness associated with anarchists and disarm all anarchist groups in the face of their militancy.[66]

From early 1918, the Bolsheviks started physical elimination of opposition, other socialist and revolutionary fractions. Anarchists were among the first:

Of all the revolutionary elements in Russia it is the Anarchists who now suffer the most ruthless and systematic persecution. Their suppression by the Bolsheviki began already in 1918, when — in the month of April of that year — the Communist Government attacked, without provocation or warning, the Anarchist Club of Moscow and by the use of machine guns and artillery "liquidated" the whole organisation. It was the beginning of Anarchist hounding, but it was sporadic in character, breaking out now and then, quite planless, and frequently self-contradictory.

Prior to the events that would officially catalyze the Red Terror,[67] Vladimir Lenin issued orders and made speeches which included harsh expressions and descriptions of brutal measures to be taken against the "class enemies", which, however, often were not actual orders or were not carried out as such. For example, in a telegram which became known as "Lenin's hanging order" he demanded and "crush" landowners in Penza and to publicly hang "at least 100 kulaks, rich bastards, and known bloodsuckers"[67] in response to an uprising there; yet, only the 13 organizers of the murder of local authorities and the uprising were arrested, while the uprising ended as propaganda activities were held there;[68] in 1920, having received information that in Estonia and Latvia, with which Soviet Russia had concluded peace treaties, volunteers were being enrolled in anti-Bolshevik detachments, Lenin offered to "advance by 10–20 miles (versts) and hang kulaks, priests, landowners" "while pretending to be greens",[69] but instead, his government confined itself to sending diplomatic notes.[68]

Leonid Kannegisser, a young military cadet of the Imperial Russian Army, assassinated Moisey Uritsky on August 17, 1918, outside the Petrograd Cheka headquarters in retaliation for the execution of his friend and other officers.[70]

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: incomplete sentence starting with 'and sought to eliminate...'. Next sentence explains 'the term', which hasn't been introduced. (August 2023) |

On August 30, the SR Fanny Kaplan unsuccessfully attempted to assassinate Lenin,[71] who sought to eliminate political dissent, opposition, and any other threat to Bolshevik power.[72] As a result of the failed attempt on Lenin's life, he began to crack down on his political enemies in an event known as the Red Terror. More broadly, the term is usually applied to Bolshevik political repression throughout the Civil War (1917–1922),[73][74][65]

During interrogation by the Cheka, she made the following statement:

My name is Fanya Kaplan. Today I shot Lenin. I did it on my own. I will not say from whom I obtained my revolver. I will give no details. I had resolved to kill Lenin long ago. I consider him a traitor to the Revolution. I was exiled to Akatui for participating in an assassination attempt against a Tsarist official in Kiev. I spent 11 years at hard labour. After the Revolution, I was freed. I favoured the Constituent Assembly and am still for it.[75]

Kaplan referenced the Bolsheviks' growing authoritarianism, citing their forcible shutdown of the Constituent Assembly in January 1918, the elections to which they had lost. When it became clear that Kaplan would not implicate any accomplices, she was executed in Alexander Garden. The order was carried out by the commander of the Kremlin, the former Baltic sailor P. D. Malkov and a group of Latvian Bolsheviks[76][page needed][non-primary source needed] on September 3, 1918, with a bullet to the back of the head.[77] Her corpse was bundled into a barrel and set alight. The order came from Yakov Sverdlov, who only six weeks earlier had ordered the murder of the Tsar and his family.[78][79]: 442

These events persuaded the government to heed Dzerzhinsky's lobbying for greater terror against opposition. The campaign of mass repressions would officially begin thereafter.[71][65] The Red Terror is considered to have officially begun between 17 and 30 August 1918.[71][65]

Revolts against grain requisitioning

Protests against grain requisitioning of the peasantry were a major component of the Tambov Rebellion and similar uprisings; Lenin's New Economic Policy was introduced as a concession.

The policies of "food dictatorship" proclaimed by the Bolsheviks in May 1918 sparked violent resistance in numerous districts of European Russia: revolts and clashes between the peasants and the Red Army were reported in Voronezh, Tambov, Penza, Saratov and in the districts of Kostroma, Moscow, Novgorod, Petrograd, Pskov and Smolensk. The revolts were bloodily crushed by the Bolsheviks: in the Voronezh Oblast, the Red Guards killed sixteen peasants during the pacification of the village, while another village was shelled with artillery in order to force the peasants to surrender and in the Novgorod Oblast the rebelling peasants were dispersed with machine-gun fire from a train sent by a detachment of Latvian Red Army soldiers.[80] While the Bolsheviks immediately denounced the rebellion as orchestrated by the SRs, there is actually no evidence that they were involved into peasant violence, which they deemed as counterproductive.[81]

Geography and chronology

In the European part of Russia the war was fought across three main fronts: the eastern, the southern and the northwestern. It can also be roughly split into the following periods.

The first period lasted from the Revolution until the Armistice, or roughly March 1917 to November 1918. Already on the date of the Revolution, Cossack General Alexey Kaledin refused to recognize it and assumed full governmental authority in the Don region,[82] where the Volunteer Army began amassing support. The signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk also resulted in direct Allied intervention in Russia and the arming of military forces opposed to the Bolshevik government. There were also many German commanders who offered support against the Bolsheviks, fearing a confrontation with them was impending as well.

During the first period, the Bolsheviks took control of Central Asia out of the hands of the Provisional Government and White Army, setting up a base for the Communist Party in the Steppe and Turkestan, where nearly two million Russian settlers were located.[83]

Most of the fighting in the first period was sporadic, involved only small groups and had a fluid and rapidly shifting strategic situation. Among the antagonists were the Czechoslovak Legion,[84] the Poles of the 4th and 5th Rifle Divisions and the pro-Bolshevik Red Latvian riflemen.

The second period of the war lasted from January to November 1919. At first the White armies' advances from the south (under Denikin), the east (under Kolchak) and the northwest (under Yudenich) were successful, forcing the Red Army and its allies back on all three fronts. In July 1919 the Red Army suffered another reverse after a mass defection of units in the Crimea to the anarchist Insurgent Army under Nestor Makhno, enabling anarchist forces to consolidate power in Ukraine. Leon Trotsky soon reformed the Red Army, concluding the first of two military alliances with the anarchists. In June the Red Army first checked Kolchak's advance. After a series of engagements, assisted by an Insurgent Army offensive against White supply lines, the Red Army defeated Denikin's and Yudenich's armies in October and November.

The third period of the war was the extended siege of the last White forces in the Crimea in 1920. General Wrangel had gathered the remnants of Denikin's armies, occupying much of the Crimea. An attempted invasion of southern Ukraine was rebuffed by the Insurgent Army under Makhno's command. Pursued into Crimea by Makhno's troops, Wrangel went over to the defensive in the Crimea. After an abortive move north against the Red Army, Wrangel's troops were forced south by Red Army and Insurgent Army forces; Wrangel and the remains of his army were evacuated to Constantinople in November 1920.

Warfare

October Revolution

In the October Revolution, the Bolshevik Party directed the Red Guard (armed groups of workers and Imperial army deserters) to seize control of Petrograd and immediately began the armed takeover of cities and villages throughout the former Russian Empire. In January 1918 the Bolsheviks dissolved the Russian Constituent Assembly and proclaimed the Soviets (workers' councils) as the new government of Russia.

Initial anti-Bolshevik uprisings

The first attempt to regain power from the Bolsheviks was made by the Kerensky-Krasnov uprising in October 1917. It was supported by the Junker Mutiny in Petrograd but was quickly put down by the Red Guard, notably including the Latvian Rifle Division.

The initial groups that fought against the Communists were local Cossack armies that had declared their loyalty to the Provisional Government. Kaledin of the Don Cossacks and General Grigory Semenov of the Siberian Cossacks were prominent among them. The leading Tsarist officers of the Imperial Russian Army also started to resist. In November, General Mikhail Alekseev, the Tsar's Chief of Staff during the First World War, began to organize the Volunteer Army in Novocherkassk. Volunteers of the small army were mostly officers of the old Russian army, military cadets and students. In December 1917, Alekseev was joined by General Lavr Kornilov, Denikin and other Tsarist officers who had escaped from the jail, where they had been imprisoned following the abortive Kornilov affair just before the Revolution.[85] On 9 December, the Military Revolutionary Committee in Rostov rebelled, with the Bolsheviks controlling the city for five days until the Alekseev Organization supported Kaledin in recapturing the city. According to Peter Kenez, "The operation, begun on December 9, can be regarded as the beginning of the Civil War."[86]

Having stated in the November 1917 "Declaration of Rights of Nations of Russia" that any nation under imperial Russian rule should be immediately given the power of self-determination, the Bolsheviks had begun to usurp the power of the Provisional Government in the territories of Central Asia soon after the establishment of the Turkestan Committee in Tashkent.[87] In April 1917 the Provisional Government set up the committee, which was mostly made up of former Tsarist officials.[88] The Bolsheviks attempted to take control of the Committee in Tashkent on 12 September 1917 but it was unsuccessful, and many leaders were arrested. However, because the Committee lacked representation of the native population and poor Russian settlers, they had to release the Bolshevik prisoners almost immediately because of a public outcry, and a successful takeover of that government body took place two months later in November.[89] The Leagues of Mohammedam Working People (which Russian settlers and natives who had been sent to work behind the lines for the Tsarist government in 1916 formed in March 1917) had led numerous strikes in the industrial centers throughout September 1917.[90] However, after the Bolshevik destruction of the Provisional Government in Tashkent, Muslim elites formed an autonomous government in Turkestan, commonly called the "Kokand autonomy" (or simply Kokand).[91] The White Russians supported that government body, which lasted several months because of Bolshevik troop isolation from Moscow.[92] In January 1918 the Soviet forces, under Lt. Col. Muravyov, invaded Ukraine and invested Kiev, where the Central Council of Ukraine held power. With the help of the Kiev Arsenal Uprising, the Bolsheviks captured the city on 26 January.[93]

Peace with the Central Powers

The Bolsheviks decided to immediately make peace with the Central Powers, as they had promised the Russian people before the Revolution.[94] Vladimir Lenin's political enemies attributed that decision to his sponsorship by the Foreign Office of Wilhelm II, German Emperor, offered to Lenin in hope that, with a revolution, Russia would withdraw from World War I. That suspicion was bolstered by the German Foreign Ministry's sponsorship of Lenin's return to Petrograd.[95] However, after the military fiasco of the summer offensive (June 1917) by the Russian Provisional Government had devastated the structure of the Russian Army, it became crucial that Lenin realize the promised peace.[96] Even before the failed summer offensive the Russian population was very skeptical about the continuation of the war. Western socialists had promptly arrived from France and from the UK to convince the Russians to continue the fight, but could not change the new pacifist mood of Russia.[97]

On 16 December 1917 an armistice was signed between Russia and the Central Powers in Brest-Litovsk and peace talks began.[98] As a condition for peace, the proposed treaty by the Central Powers conceded huge portions of the former Russian Empire to the German Empire and the Ottoman Empire, greatly upsetting nationalists and conservatives. Leon Trotsky, representing the Bolsheviks, refused at first to sign the treaty while continuing to observe a unilateral cease-fire, following the policy of "No war, no peace".[99]

Therefore, on 18 February 1918, the Germans began Operation Faustschlag on the Eastern Front, encountering virtually no resistance in a campaign that lasted 11 days.[99] Signing a formal peace treaty was the only option in the eyes of the Bolsheviks because the Russian Army was demobilized, and the newly formed Red Guard could not stop the advance. The Soviets acceded to a peace treaty, and the formal agreement, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, was ratified on 3 March. The Soviets viewed the treaty as merely a necessary and expedient means to end the war.

Ukraine, South Russia, and Caucasus (1918)

In Ukraine, the German-Austrian Operation Faustschlag had by April 1918 removed the Bolsheviks from Ukraine.[100][101][102][103] The German and Austro-Hungarian victories in Ukraine were caused by the apathy of the locals and the inferior fighting skills of Bolsheviks troops to their Austro-Hungarian and German counterparts.[103]

Under Soviet pressure, the Volunteer Army embarked on the epic Ice March from Yekaterinodar to Kuban on 22 February 1918, where they joined with the Kuban Cossacks to mount an abortive assault on Yekaterinodar.[104] The Soviets recaptured Rostov on the next day.[104] Kornilov was killed in the fighting on 13 April, and Denikin took over command. Fighting off its pursuers without respite, the army succeeded in breaking its way through back towards the Don by May, where the Cossack uprising against the Bolsheviks had started.[105]

The Baku Soviet Commune was established on 13 April. Germany landed its Caucasus Expedition troops in Poti on 8 June. The Ottoman Army of Islam (in coalition with Azerbaijan) drove them out of Baku on 26 July 1918. Subsequently, the Dashanaks, Right SRs and Mensheviks started negotiations with Gen. Dunsterville, the commander of the British troops in Persia. The Bolsheviks and their Left SR allies were opposed to it, but on 25 July the majority of the Soviets voted to call in the British and the Bolsheviks resigned. The Baku Soviet Commune ended its existence and was replaced by the Central Caspian Dictatorship.

In June 1918 the Volunteer Army, numbering some 9,000 men, started its Second Kuban campaign, capturing Yekaterinodar on 16 August, followed by Armavir and Stavropol. By early 1919, they controlled the Northern Caucasus.[106]

On 8 October, Alekseev died. On 8 January 1919, Denikin became the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces of South Russia, uniting the Volunteer Army with Pyotr Krasnov's Don Army. Pyotr Wrangel became Denikin's Chief of Staff.[107]

In December, three-fourths of the army was in the Northern Caucasus. That included three thousand of Vladimir Liakhov's soldiers around Vladikavkaz, thirteen thousand soldiers under Wrangel and Kazanovich in the center of the front, Stankevich's almost three thousand men with the Don Cossacks, while Vladimir May-Mayevsky's three thousand were sent to the Donets basin, and de Bode commanded two thousand in Crimea.[108]

Eastern Russia, Siberia and the Far East (1918)

The revolt of the Czechoslovak Legion broke out in May 1918, and proceeded to occupy the Trans-Siberian Railway from Ufa to Vladivostok. Uprisings overthrew other Bolshevik towns. On 7 July, the western portion of the legion declared itself to be a new eastern front, anticipating allied intervention. According to William Henry Chamberlin, "Two governments emerged as a result of the first successes of the Czechs: the West Siberian Commissariat and the Government of the Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly in Samara." On 17 July, shortly before the fall of Yekaterinburg, the former tsar and his family were murdered.[109]

The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries supported peasants fighting against Soviet control of food supplies.[110] In May 1918, with the support of the Czechoslovak Legion, they took Samara and Saratov, establishing the Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly—known as the "Komuch". By July the authority of the Komuch extended over much of the area controlled by the Czechoslovak Legion. The Komuch pursued an ambivalent social policy, combining democratic and socialist measures, such as the institution of an eight-hour working day, with "restorative" actions, such as returning both factories and land to their former owners. After the fall of Kazan, Vladimir Lenin called for the dispatch of Petrograd workers to the Kazan Front: "We must send down the maximum number of Petrograd workers: (1) a few dozen 'leaders' like Kayurov; (2) a few thousand militants 'from the ranks'".

After a series of reverses at the front, the Bolsheviks' War Commissar, Trotsky, instituted increasingly harsh measures in order to prevent unauthorised withdrawals, desertions, and mutinies in the Red Army. In the field, the Cheka Special Investigations Forces (termed the Special Punitive Department of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combat of Counter-Revolution and Sabotage or Special Punitive Brigades) followed the Red Army, conducting field tribunals and summary executions of soldiers and officers who deserted, retreated from their positions, or failed to display sufficient offensive zeal.[111][112] The Cheka Special Investigations Forces were also charged with the detection of sabotage and counter-revolutionary activity by Red Army soldiers and commanders. Trotsky extended the use of the death penalty to the occasional political commissar whose detachment retreated or broke in the face of the enemy.[113] In August, frustrated at continued reports of Red Army troops breaking under fire, Trotsky authorised the formation of barrier troops – stationed behind unreliable Red Army units and given orders to shoot anyone withdrawing from the battle line without authorisation.[114]

In September 1918, the Komuch, the Siberian Provisional Government, and other anti-Bolshevik Russians agreed during the State Meeting in Ufa to form a new Provisional All-Russian Government in Omsk, headed by a Directory of five: two Socialist-Revolutionaries. Nikolai Avksentiev and Vladimir Zenzinov, the Kadet lawyer V. A. Vinogradov, Siberian Premier Vologodskii, and General Vasily Boldyrev.[115]

By the fall of 1918, anti-Bolshevik White forces in the east included the People's Army (Komuch), the Siberian Army (of the Siberian Provisional Government) and insurgent Cossack units of Orenburg, the Urals, Siberia, Semirechye, Baikal, and Amur and Ussuri Cossacks, nominally under the orders of Gen. V.G. Boldyrev, Commander-in-Chief, appointed by the Ufa Directorate.

On the Volga, Col. Kappel's White detachment captured Kazan on 7 August, but Red Forces recaptured the city on 8 September 1918 following a counteroffensive. On the 11th Simbirsk fell, and on 8 October Samara. The Whites fell back eastwards to Ufa and Orenburg.

In Omsk, the Russian Provisional Government quickly came under the influence and later the dominance of its new War Minister, the rear-admiral Kolchak. On 18 November, a coup d'état established Kolchak as supreme leader. Two members of the Directory were arrested, and subsequently deported, while Kolchak was proclaimed "Supreme Ruler", and "Commander-in-Chief of all Land and Naval Forces of Russia."[116] By mid-December 1918, the White armies had to leave Ufa, but they balanced that failure with a successful drive towards Perm, which they took on 24 December.

Barrier troops

In the Red Army, the concept of barrier troops first arose in August 1918 with the formation of the заградительные отряды (zagraditelnye otriady), translated as "blocking troops" or "anti-retreat detachments" (Russian: заградотряды, заградительные отряды, отряды заграждения).[117] The barrier troops comprised personnel drawn from the Cheka punitive detachments or from regular Red Army infantry regiments.

The first use of the barrier troops by the Red Army occurred in the late summer and fall of 1918 in the Eastern front during the Russian Civil War, when Leon Trotsky authorized Mikhail Tukhachevsky, the commander of the 1st Army, to station blocking detachments behind unreliable Red Army infantry regiments in the 1st Red Army, with orders to shoot if front-line troops either deserted or retreated without permission.[117]

In December 1918, Trotsky ordered that detachments of additional barrier troops be raised for attachment to each infantry formation in the Red Army. On December 18 he cabled:

How do things stand with the blocking units? As far as I am aware they have not been included in our establishment and it appears they have no personnel. It is absolutely essential that we have at least an embryonic network of blocking units and that we work out a procedure for bringing them up to strength and deploying them.[117]

In 1919, 616 "hardcore" deserters of the total 837,000 draft dodgers and deserters were executed following Trotsky's draconian measures.[118] According to Figes, "a majority of deserters (most registered as "weak-willed") were handed back to the military authorities, and formed into units for transfer to one of the rear armies or directly to the front". Even those registered as "malicious" deserters were returned to the ranks when the demand for reinforcements became desperate". Forges also noted that the Red Army instituted amnesty weeks to prohibit punitive measures against desertion which encouraged the voluntary return of 98,000-132,000 deserters to the army.[119]

The barrier troops were also used to enforce Bolshevik control over food supplies in areas controlled by the Red Army as part of Lenin's war communism policies, a role which soon earned them the hatred of the Russian civilian population.[120] These policies in part led to the Russian famine of 1921–1922, which killed about five million people.[121][122] However, the famine was preceded by bad harvests, harsh winter, drought especially in the Volga Valley which was exacerbated by a range of factors including the war, the presence of the White Army and the methods of war communism.[123] The outbreaks of diseases such as cholera and typhus were also contributing factors to the famine casualties.[124][125]

Central Asia (1918)

In February 1918, the Red Army overthrew the White Russian-supported Kokand Autonomy of Turkestan.[126] Although that move seemed to solidify Bolshevik power in Central Asia, more troubles soon arose for the Red Army as the Allied Forces began to intervene. British support of the White Army provided the greatest threat to the Red Army in Central Asia during 1918. Britain sent three prominent military leaders to the area. One was Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Marshman Baile, who recorded a mission to Tashkent, from where the Bolsheviks forced him to flee. Another was General Wilfrid Malleson, leading the Malleson Mission, who assisted the Mensheviks in Ashkhabad (now the capital of Turkmenistan) with a small Anglo-Indian force. However, he failed to gain control of Tashkent, Bukhara and Khiva. The third was Major General Dunsterville, who was driven out by the Bolsheviks of Central Asia only a month after his arrival in August 1918.[127] Despite setbacks as a result of British invasions during 1918, the Bolsheviks continued to make progress in bringing the Central Asian population under their influence. The first regional congress of the Russian Communist Party convened in the city of Tashkent in June 1918 in order to build support for a local Bolshevik Party.[128]

Left SR Uprising

On 6 July 1918, two Left Socialist-Revolutionaries and Cheka employees, Yakov Blumkin and Nikolai Andreyev, assassinated the German ambassador, Count Mirbach. In Moscow a Left SR uprising was put down by the Bolsheviks, mass arrests of Socialist-Revolutionaries followed, and executions became more frequent. Chamberlin noted, "The time of relative leniency toward former fellow-revolutionists was over. The Left Socialist Revolutionaries, of course, were no longer tolerated as members of the Soviets; from this time the Soviet regime became a pure and undiluted dictatorship of the Communist Party." Similarly, Boris Savinkov's surprise attacks were suppressed, with many of the conspirators being executed, as "Mass Red Terror" became a reality.[129]

Estonia, Latvia and Petrograd

Estonia cleared its territory of the Red Army by January 1919.[130] Baltic German volunteers captured Riga from the Red Latvian Riflemen on 22 May, but the Estonian 3rd Division defeated the Baltic Germans a month later, aiding the establishment of the Republic of Latvia.[131]

That rendered possible another threat to the Red Army, from General Yudenich, who had spent the summer organizing the Northwestern Army in Estonia with local and British support. In October 1919, he tried to capture Petrograd in a sudden assault with a force of around 20,000 men. The attack was well-executed, using night attacks and lightning cavalry maneuvers to turn the flanks of the defending Red Army. Yudenich also had six British tanks, which caused panic whenever they appeared. The Allies gave large quantities of aid to Yudenich, but he complained of receiving insufficient support.

By 19 October, Yudenich's troops had reached the outskirts of the city. Some members of the Bolshevik central committee in Moscow were willing to give up Petrograd, but Trotsky refused to accept the loss of the city and personally organized its defenses. Trotsky himself declared, "It is impossible for a little army of 15,000 ex-officers to master a working-class capital of 700,000 inhabitants." He settled on a strategy of urban defense, proclaiming that the city would "defend itself on its own ground" and that the White Army would be lost in a labyrinth of fortified streets and there "meet its grave".[132]

Trotsky armed all available workers, men and women, and ordered the transfer of military forces from Moscow. Within a few weeks, the Red Army defending Petrograd had tripled in size and outnumbered Yudenich three to one. Yudenich, short of supplies, then decided to call off the siege of the city and withdrew. He repeatedly asked permission to withdraw his army across the border to Estonia. However, units retreating across the border were disarmed and interned by orders of the Estonian government, which had entered into peace negotiations with the Soviet Government on 16 September and had been informed by the Soviet authorities of their 6 November decision that if the White Army was allowed to retreat into Estonia, it would be pursued across the border by the Reds.[133] In fact, the Reds attacked Estonian army positions and fighting continued until a ceasefire went into effect on 3 January 1920. After the Treaty of Tartu, most of Yudenich's soldiers went into exile. Former Imperial Russian and then Finnish General Mannerheim planned an intervention to help the Whites in Russia capture Petrograd. However, he did not gain the necessary support for the endeavour. Lenin considered it "completely certain, that the slightest aid from Finland would have determined the fate of [the city]".

Northern Russia (1919)

The British occupied Murmansk and seized Arkhangelsk alongside United States forces. With the retreat of Kolchak in Siberia, they pulled their troops out of the cities before the winter trapped them in the port. The remaining White forces under Yevgeny Miller evacuated the region in February 1920.[134]

Siberia (1919)

At the beginning of March 1919, the general offensive of the Whites on the eastern front began. Ufa was retaken on 13 March; by mid-April, the White Army stopped at the Glazov–Chistopol–Bugulma–Buguruslan–Sharlyk line. Reds started their counteroffensive against Kolchak's forces at the end of April. The Red 5th Army, led by the capable commander Tukhachevsky, captured Elabuga on 26 May, Sarapul on 2 June and Izevsk on the 7th and continued to push forward. Both sides had victories and losses, but by the middle of summer the Red Army was larger than the White Army and had managed to recapture territory previously lost.[135]

Following the abortive offensive at Chelyabinsk, the White armies withdrew beyond the Tobol. In September 1919 a White offensive was launched against the Tobol Front, the last attempt to change the course of events. However, on 14 October the Reds counterattacked, and thus began the uninterrupted retreat of the Whites to the east. On 14 November 1919 the Red Army captured Omsk.[136] Adm. Kolchak lost control of his government shortly after the defeat; White Army forces in Siberia had essentially ceased to exist by December. Retreat of the eastern front by White armies lasted three months, until mid-February 1920, when the survivors, after crossing Lake Baikal, reached the Chita area and joined Ataman Semenov's forces.

South Russia (1919)

The Cossacks had been unable to organise and capitalise on their successes at the end of 1918. By 1919 they had begun to run short of supplies. Consequently, when the Soviet Russian counteroffensive began in January 1919 under the Bolshevik commander Antonov-Ovseenko, the Cossack forces rapidly fell apart. The Red Army captured Kiev on 3 February 1919.[137]

Denikin's military strength continued to grow in 1919, with significant munitions supplied by the British empire. In January, Denikin's Armed Forces of South Russia (AFSR) completed the elimination of Red forces in the northern Caucasus and moved north, in an effort to protect the Don district.[138]

On 18 December 1918, French forces landed in Odessa and Crimea, but evacuated Odessa on 6 April 1919, and the Crimea by the end of the month. According to Chamberlin, "France gave far less practical aid to the Whites than did England; its sole independent venture in intervention, at Odessa, ended in a complete fiasco."[139]

Denikin then reorganized the Armed Forces of South Russia under the leadership of Vladimir May-Mayevsky, Vladimir Sidorin, and Pyotr Wrangel. On 22 May, Wrangel's Caucasian army defeated the 10th Army (RSFSR) in the battle for Velikoknyazheskaya, and then captured Tsaritsyn on 1 July. Sidorin advanced north toward Voronezh, increasing his army's strength in the process. On 25 June, May–Mayevsky captured Kharkov, and then Ekaterinoslav on 30 June, which forced the Reds to abandon Crimea. On 3 July, Denikin issued his Moscow directive, in which his armies would converge on Moscow.[140]

Although Britain had withdrawn its own troops from the theatre, it continued to give significant military aid (money, weapons, food, ammunition and some military advisers) to the White Armies during 1919. Major Ewen Cameron Bruce of the British Army had volunteered to command a British tank mission assisting the White Army. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order[141] for his bravery during the June 1919 Battle of Tsaritsyn for single-handedly storming and capturing the fortified city of Tsaritsyn, under heavy shell fire in a single tank, which led to the capture of over 40,000 prisoners.[142] The fall of Tsaritsyn is viewed "as one of the key battles of the Russian Civil War" and greatly helped the White Russian cause.[142] The notable historian Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart comments that Bruce's tank action during the battle is to be seen as "one of the most remarkable feats in the whole history of the Tank Corps".[143]

On 14 August, the Bolsheviks launched their Southern Front counteroffensive. After six weeks of heavy fighting the counteroffensive failed, and Denikin was able to capture more territory. By November, White Forces had reached the Zbruch, the Ukrainian-Polish border.[144]

Denikin's forces constituted a real threat and for a time threatened to reach Moscow. The Red Army, stretched thin by fighting on all fronts, was forced out of Kiev on 30 August. Kursk and Orel were taken, on 20 September and 14 October, respectively. The latter, only 205 miles (330 km) from Moscow, was the closest the AFSR would come to its target.[145] The Cossack Don Army under the command of General Vladimir Sidorin continued north towards Voronezh, but Semyon Budyonny's cavalrymen defeated them there on 24 October. That allowed the Red Army to cross the Don River, threatening to split the Don and Volunteer Armies. Fierce fighting took place at the key rail junction of Kastornoye, which was taken on 15 November. Kursk was retaken two days later.[146]

Kenez states, "In October Denikin ruled more than forty million people and controlled the economically most valuable parts of the Russian Empire." Yet, "The White armies, which had fought victoriously during the summer and early fall, fell back in disorder in November and December." Denikin's front line was overstretched, while his reserves dealt with Makhno's anarchists in the rear. Between September and October, the Reds mobilized one hundred thousand new soldiers and adopted the Trotsky-Vācietis strategy with the Ninth and Tenth armies forming V. I. Shorin's Southeastern Front between Tsaritsyn and Bobrov, while the Eighth, Twelfth, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth armies formed A. I. Egorov's Southern Front between Zhitomir and Bobrov. Sergey Kamenev was in overall command of the two fronts. On Denikin's left was Abram Dragomirov, while in his center was Vladimir May-Mayevsky's Volunteer Army, Vladimir Sidorin's Don Cossacks were further east, with Wrangel's Caucasian army at Tsaritsyn, and an additional was in the Northern Caucasus attempting to capture Astrakhan. On 20 October, May–Mayevsky was forced to evacuate Orel during the Orel-Kursk operation. On 24 October, Semyon Budyonny captured Voronezh, and Kursk on 15 November, during the Voronezh-Kastornoye operation (1919). On 6 January, the Reds reached the Black Sea at Mariupol and Taganrog, and on 9 January, they reached Rostov. According to Kenez, "The Whites had now lost all the territories which they had captured in 1919, and held approximately the same area in which they had started two years before."[147]

Central Asia (1919)

By February 1919 the British government had pulled its military forces out of Central Asia.[148] Despite the success for the Red Army, the White Army's assaults in European Russia and other areas broke communication between Moscow and Tashkent. For a time, Central Asia was completely cut off from Red Army forces in Siberia.[149] Although the communication failure weakened the Red Army, the Bolsheviks continued their efforts to gain support for the Bolshevik Party in Central Asia by holding a second regional conference in March. During the conference, a regional bureau of Muslim organisations of the Russian Bolshevik Party was formed. The Bolshevik Party continued to try to gain support among the native population by giving it the impression of better representation for the Central Asian population and throughout the end of the year could maintain harmony with the Central Asian people.[150]

Communication difficulties with Red Army forces in Siberia and European Russia ceased to be a problem by mid-November 1919. Red Army successes north of Central Asia caused communication with Moscow to be re-established and the Bolsheviks to claim victory over the White Army in Turkestan.[149]

In the Ural-Guryev operation of 1919–1920, the Red Turkestan Front defeated the Ural Army. During winter 1920, Ural Cossacks and their families, totaling about 15,000 people, headed south along the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea towards Fort Alexandrovsk. Only a few hundred of them reached Persia in June 1920.[151] The Orenburg Independent Army was formed from Orenburg Cossacks and other troops who rebelled against the Bolsheviks. During the winter 1919–20, the Orenburg Army retreated to Semirechye in what is known as the Starving March, as half of the participants perished.[152] In March 1920 her remnants crossed the border into the Northwestern region of China.

South Russia, Ukraine and Kronstadt (1920–21)

At the beginning of 1920, Denikin was reduced to defending Novorossia, the Crimean peninsula, and the Northern Caucasus. On 26 January, the Caucasian army retreated beyond the Manych. On 7 February, the Reds occupied Odessa, but then Makhno's anarchists started fighting the Fourteenth Red Army. On 20 February, Denikin succeeded in recapturing Rostov, his last victory, before giving it up soon after.[153]

By the beginning of 1920, the main body of the Armed Forces of South Russia was rapidly retreating towards the Don, to Rostov. Denikin hoped to hold the crossings of the Don, then rest and reform his troops, but the White Army was not able to hold the Don area, and at the end of February 1920 started a retreat across Kuban towards Novorossiysk. Slipshod evacuation of Novorossiysk proved to be a dark event for the White Army. Russian and Allied ships evacuated about 40,000 of Denikin's men from Novorossiysk to the Crimea, without horses or any heavy equipment, while about 20,000 men were left behind and either dispersed or were captured by the Red Army. Following the disastrous Novorossiysk evacuation, Denikin stepped down and the military council elected Wrangel as the new Commander-in-Chief of the White Army. He was able to restore order to the dispirited troops and reshape an army that could fight as a regular force again. It remained an organized force in the Crimea throughout 1920.[154]

After Moscow's Bolshevik government signed a military and political alliance with Nestor Makhno and the Ukrainian anarchists, the Insurgent Army attacked and defeated several regiments of Wrangel's troops in southern Ukraine, forcing him to retreat before he could capture that year's grain harvest.[155]

Stymied in his efforts to consolidate his hold, Wrangel then attacked north in an attempt to take advantage of recent Red Army defeats at the close of the Polish–Soviet War of 1919–1920. The Red Army eventually halted the offensive, and Wrangel's troops had to retreat to Crimea in November 1920, pursued by both the Red and Black cavalry and infantry. Wrangel's fleet evacuated him and his army to Constantinople on 14 November 1920, ending the struggle of Reds and Whites in Southern Russia.[137]

After the defeat of Wrangel, the Red Army immediately repudiated its 1920 treaty of alliance with Nestor Makhno and attacked the anarchist Insurgent Army; the campaign to liquidate Makhno and the Ukrainian anarchists began with an attempted assassination of Makhno by Cheka agents. Anger at continued repression by the Bolshevik Communist government and at its liberal use of the Cheka to put down anarchist elements led to a naval mutiny at Kronstadt in March 1921, followed by peasant revolts – all of which were put down by the Bolsheviks. The outset of the year was marked by strikes and demonstrations – in both Moscow and Petrograd, as well as the countryside – due to discontent with the results of policies that made up war communism.[156][157] The Bolsheviks, in response to the protests, enacted martial law and sent the Red Army to disperse the workers.[158][159] This was followed up by mass arrests executed by the Cheka.[160] Repression and minor concessions only temporarily quelled the discontent as Petrograd protests continued that year in March. This time the factory workers were joined by sailors stationed on the nearby island-fort of Kronstadt.[161] Disappointed in the direction of the Bolshevik government, the rebels demanded a series of reforms including: reduction in Bolshevik privileges, newly elected soviets to include socialist and anarchist groups, economic freedom for peasants and workers, dissolution of the bureaucratic governmental organs created during the civil war, and the restoration of worker rights for the working class.[162] The workers and sailors of the Kronstadt rebellion were promptly crushed by Red Army forces, with a thousand rebels killed in battle and another thousand executed the following weeks, with many more fleeing abroad and to the countryside.[163][164][165] These events coincided with the 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks). There, Lenin argued that the soviets and the principle of democratic centralism within the Bolshevik party still assured democracy. However, faced with support for Kronstadt within Bolshevik ranks, Lenin also issued a "temporary" ban on factions in the Russian Communist Party. This ban remained until the revolutions of 1989 and, according to some critics, made the democratic procedures within the party an empty formality, and helped Stalin to consolidate much more authority under the party. Soviets were transformed into the bureaucratic structure that existed for the rest of the history of the Soviet Union and were completely under the control of party officials and the politburo.[b] Red Army attacks on the anarchist forces and their sympathisers increased in ferocity throughout 1921.[166]

Siberia and the Far East (1920–22)

In Siberia, Admiral Kolchak's army had disintegrated. He himself gave up command after the loss of Omsk and designated Gen. Grigory Semyonov as the new leader of the White Army in Siberia. Not long afterward, Kolchak was arrested by the disaffected Czechoslovak Legion as he traveled towards Irkutsk without the protection of the army and was turned over to the socialist Political Centre in Irkutsk. Six days later, the regime was replaced by a Bolshevik-dominated Military-Revolutionary Committee. On 6–7 February Kolchak and his prime minister Victor Pepelyaev were shot, and their bodies were thrown through the ice of the frozen Angara River, just before the arrival of the White Army in the area.[167]

Remnants of Kolchak's army reached Transbaikalia and joined Semyonov's troops, forming the Far Eastern army. With the support of the Japanese army, it was able to hold Chita, but after the withdrawal of Japanese soldiers from Transbaikalia, Semenov's position became untenable and in November 1920 he was driven by the Red Army from Transbaikalia and took refuge in China. The Japanese, who had plans to annex the Amur Krai, finally pulled their troops out as Bolshevik forces gradually asserted control over the Russian Far East. On 25 October 1922 Vladivostok fell to the Red Army, and the Provisional Priamur Government was extinguished.

Aftermath

With the end of the war, the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) no longer faced an acute military threat to its existence and power. However, the perceived threat of continued popular discontent, combined with the failure of socialist revolutions in other countries, such as the German revolution of 1918–1919, contributed to the continued militarization of Soviet society.

The Bolsheviks managed to consolidate control over Russia, but were only partially successful at re-establishing territorial control of the other provinces of the former Russian Empire. The treaty of Riga, which was signed in March 1921 after the Polish–Soviet War, split the territories in Belarus and Ukraine between the Republic of Poland and Soviet Russia. Estonia, Finland, Latvia, and Lithuania all repelled Soviet invasions, while Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia were occupied by the Red Army.[15][16] In 1925, the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) changed its name to the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks).

Evacuations

Around one to two million people known as the White émigrés fled Russia, many with General Wrangel, some through the Far East and others west into the newly independent Baltic countries. The émigrés included a large percentage of the educated and skilled population of Russia.[168]

Ensuing rebellion

In Central Asia, Red Army troops continued to face resistance into 1923, where basmachi (armed bands of Islamic guerrillas) had formed to fight the Bolshevik takeover. The Soviets engaged non-Russian peoples in Central Asia, like Magaza Masanchi, commander of the Dungan Cavalry Regiment, to fight against the Basmachis. The Communist Party did not completely dismantle the group until 1934.[169]

General Anatoly Pepelyayev continued armed resistance in the Ayano-Maysky District until June 1923. The regions of Kamchatka and Northern Sakhalin remained under Japanese occupation until their treaty with the Soviet Union in 1925, when their forces were finally withdrawn.

Casualties

The results of the civil war were momentous. Soviet demographer Boris Urlanis estimated that 300,000 men were killed in action during the Civil War and Polish-Soviet War – 125,000 in the Red Army, 175,500 White armies and Poles – and the total number of military personnel from both sides dead from disease as 450,000.[170] Boris Sennikov estimated the total losses among the population of Tambov region in 1920 to 1922 resulting from the war, executions, and imprisonment in concentration camps as approximately 240,000.[171] By 1922, there were at least 7,000,000 street children in Russia as a result of nearly ten years of devastation from World War I and the civil war.[172]

At the end of the Civil War the Russian SFSR was exhausted and near ruin. The droughts of 1920 and 1921, as well as the Russian famine of 1921, worsened the disaster still further, killing roughly 5 million people. Disease had reached pandemic proportions, with 3,000,000 dying of typhus throughout the war. Millions more also died of widespread starvation, wholesale massacres by both sides and pogroms against Jews in Ukraine and southern Russia.[173]

Civilian casualties

As many as 10 million people died as a result of the Russian Civil War, and the overwhelming majority of these were civilian casualties.[174] There is no consensus among the Western historians on the number of deaths from the Red Terror. One source gives estimates of 28,000 executions per year from December 1917 to February 1922.[175] Estimates for the number of people shot during the initial period of the Red Terror are at least 10,000.[176] Estimates for the whole period go for a low of 50,000[177] to highs of 140,000[177][178] and 200,000 executed.[179] Most estimations for the number of executions in total put the number at about 100,000.[180] According to Vadim Erlikhman's investigation, the number of the Red Terror's victims is at least 1,200,000 people.[181] According to Robert Conquest, a total of 140,000 people were shot in 1917–1922, but Jonathan D. Smele estimates they were considerably fewer, "perhaps less than half that many".[182] Candidate of Historical Sciences Nikolay Zayats states that the number of people shot by the Cheka in 1918–1922 is about 37,300 people, shot in 1918–1921 by the verdicts of the tribunals — 14,200, i.e. about 50,000–55,000 people in total, although executions and atrocities were not limited to the Cheka, having been organized by the Red Army as well.[183][184] In 1924, an anti-Bolshevik Popular Socialist Sergei Melgunov (1879–1956) published a detailed account on the Red Terror in Russia, where he cited Professor Charles Saroléa's estimates of 1,766,188 deaths from the Bolshevik policies. He questioned the accuracy of the figures, but endorsed Saroléa's "characterisation of terror in Russia", stating it matches reality.[185][186] Modern historian Sergei Volkov, assessing the Red Terror as the entire repressive policy of the Bolsheviks during the years of the Civil War (1917–1922), estimates the direct death toll of the Red Terror at 2 million people.[187] Volkov's calculations, however, do not appear to have been confirmed by other major scholars.[c]

Ethnic violence

Some 10,000–500,000 Cossacks were killed or deported during Decossackization, out of a population of around three million.[189] An estimated 100,000 Jews were killed in Ukraine.[190] Punitive organs of the All Great Don Cossack Host sentenced 25,000 people to death between May 1918 and January 1919.[191] Kolchak's government shot 25,000 people in Ekaterinburg province alone.[192] The White Terror, as it would become known, killed about 300,000 people in total.[193]

Economic impact

The civil war had a devastating impact on the Russian economy. A black market emerged in Russia, despite the threat of martial law against profiteering. The ruble collapsed, with barter increasingly replacing money as a medium of exchange[194] and, by 1921, heavy industry output had fallen to 20% of 1913 levels. 90% of wages were paid with goods rather than money.[195] 70% of locomotives were in need of repair,[196] and food requisitioning, combined with the effects of seven years of war and a severe drought, contributed to a famine that caused between 3 and 10 million deaths.[197] Coal production decreased from 27.5 million tons (1913) to 7 million tons (1920), while overall factory production also declined from 10,000 million roubles to 1,000 million roubles. According to the noted historian David Christian, the grain harvest was also slashed from 80.1 million tons (1913) to 46.5 million tons (1920).[198]

War communism saved the Soviet government during the Civil War, but much of the Russian economy had ground to a standstill. Some peasants responded to food requisitions by refusing to till the land. By 1921, cultivated land had shrunk to 62% of the pre-war area, and the harvest yield was only about 37% of normal. The number of horses declined from 35 million in 1916 to 24 million in 1920 and cattle from 58 to 37 million. The exchange rate with the US dollar declined from two roubles in 1914 to 1,200 Rbls in 1920. Although Russia experienced extremely rapid economic growth[199] in the 1930s, the combined effect of World War I and the Civil War left a lasting scar on Russian society and had permanent effects on the development of the Soviet Union.

Political impact

The complete failure of the Communist International-inspired revolutions was a sobering experience in Moscow, and the Bolsheviks moved from world revolution to socialism in one country, the Soviet Union.[200]

The Treaty of Rapallo (1922) was an agreement signed on 16 April 1922 between the Weimar Republic and Soviet Union, under which both renounced all territorial and financial claims against each other and opened friendly diplomatic relations.[201]

In fiction

Literature

The Civil War was a popular theme among the Socialist realism writers; it was championed in the works of such authors as Dmitri Furmanov (Chapayev, 1923), Alexander Serafimovich, Vsevolod Vishnevsky (An Optimistic Tragedy, 1933) and Aleksandr Fadeyev; one of the best-known examples is the novel How the Steel Was Tempered (1934) by Nikolai Ostrovsky.

- The Road to Calvary (1922–1941) by Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy.

Other prominent works of fiction by the Soviet writers that didn't follow the methods and doctrine of Socialist realism include:

- The White Guard (1925) and A Young Doctor's Notebook (1925–1926) by Mikhail Bulgakov

- Red Cavalry (1926–1933) by Isaac Babel

- Chevengur (1927, fully published in 1971) by Andrei Platonov

- Quiet Flows the Don (1928–1940) by Mikhail Sholokhov

- Conquered City (1932) by Victor Serge

- Doctor Zhivago (1957) by Boris Pasternak

- The Red Wheel (1971–1991) by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

by the White émigré authors:

- An Evening with Claire (1930) by Gaito Gazdanov

- Novel with Cocaine (1934) by M. Ageyev

Works by the Western and contemporary authors:

- Futility (1922) by William Gerhardie

- Coup de Grâce (1939) by Marguerite Yourcenar

- Byzantium Endures (1981) by Michael Moorcock

- Fall of Giants (2010) by Ken Follett

- Bro (2011) by Vladimir Sorokin

- A Splendid Little War (2012) by Derek Robinson (novelist)

Film

- Arsenal (1928)

- Storm Over Asia (1928)

- Chapaev (1934)

- Thirteen (1936), directed by Mikhail Romm

- We Are from Kronstadt (1936), directed by Yefim Dzigan

- Knight Without Armour (1937)

- The Year 1919 (1938), directed by Ilya Trauberg

- The Baltic Marines (1939), directed by A. Faintsimmer

- Shchors (1939), directed by Dovzhenko

- Pavel Korchagin (1956), directed by A. Alov and V. Naumov

- The Forty-First (1956), directed by Grigori Chukhrai

- The Communist (film) (1957), directed by Yuli Raizman

- And Quiet Flows the Don (1958), directed by Sergei Gerasimov

- Doctor Zhivago (1965), directed by David Lean

- The Elusive Avengers (1966)

- The Red and the White (1967)

- White Sun of the Desert (1970)

- The Flight (1970), directed by A. Alov and V. Naumov

- Reds (1981), directed by Warren Beatty

- Corto Maltese in Siberia (2002)

- Nine Lives of Nestor Makhno (2005/2007)

- Admiral (2008)

- Sunstroke (2014), directed by Nikita Mikhalkov

Video games

See also

- Bibliography of the Russian Revolution and Civil War

- Index of articles related to the Russian Revolution and Civil War

- Nikolayevsk incident

- Revolutionary Mass Festivals

- Timeline of the Russian Civil War

- Pro-independence movements in the Russian Civil War

Notes

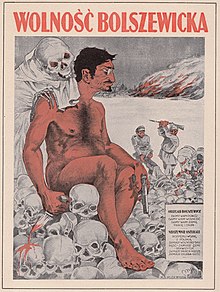

- ^

Small caption in the lower right corner reads:

The Bolsheviks promised:

We'll give you peace

We'll give you freedom

We'll give you land

Work and bread

Despicably they cheated

They started a war

With Poland

Instead of freedom they brought

The fist

Instead of land – confiscation

Instead of work – misery

Instead of bread – famine. - ^ See note regarding Library of Congress Country Studies. Chapter 7 – The Communist Party. Democratic Centralism.[citation needed]

- ^ In particular, they seem quite at odds with the demographic considerations elaborated by Italian historian and professor Andrea Graziosi in the light of the good quality Tsarist and early Soviet statistics. According to him, the excess deaths between 1914 and 1922 were about 16 million, of which 4–5 were military, the rest civilian; the overwhelming majority of the latter resulted from "starvation, typhus, epidemics, the Spanish flu and the famine of 1921–22", the roughly number of "victims of the various kinds of terror, and red and white repressions" amounting to a few hundred thousand— which is indeed a dreadful number in itself, however.[188]

References

Citations

- ^ Mawdsley 2007, pp. 3, 230.

- ^ "Russian Civil War". Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 May 2024.

- ^ Murphy, Brian (2 August 2004). Rostov in the Russian Civil War, 1917-1920: The Key to Victory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-27129-0.

- ^ Bullock, David (6 June 2014). The Russian Civil War 1918–22. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-472-81032-8 – via Google Books.

- ^ Erickson 1984, p. 763.

- ^ Belash, Victor & Belash, Aleksandr, Dorogi Nestora Makhno, p. 340

- ^ Damien Wright, Churchill's Secret War with Lenin: British and Commonwealth Military Intervention in the Russian Civil War, 1918–20, Solihull, UK, 2017, pp. 394, 526–528, 530–535; Clifford Kinvig, Churchill's Crusade: The British Invasion of Russia 1918–1920, London 2006, ISBN 1-852-85477-4, p. 297; Timothy Winegard, The First World Oil War, University of Toronto Press (2016), p. 229

- ^ Humphreys 1996, p. 26.

- ^ Tucker & Roberts 2005, p. 547.

- ^ Krivosheev et al. 1993, p. 12-13.

- ^ Smele 2016, p. 160.

- ^ Russian Civil War Archived 26 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopædia Britannica Online 2012

- ^ Leggett 1981, p. 184; Service 2000, p. 402; Read 2005, p. 206.

- ^ Hall 2015, p. 83.

- ^ a b Lee 2003, pp. 84, 88.

- ^ a b Goldstein 2013, p. 50.

- ^ Hall 2015, p. 84.

- ^ Mawdsley 2007, p. 287.

- ^ Shukman, Harold (5 December 1994). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the Russian Revolution. John Wiley & Sons. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-631-19525-2.

- ^ Bergman, Jay (2019). The French Revolutionary Tradition in Russian and Soviet Politics, Political Thought, and Culture. Oxford University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-19-884270-5.