Columbus County, North Carolina

Columbus County | |

|---|---|

Columbus County Courthouse in Whiteville | |

| Motto: "We are ready to grow with you." | |

Location within the U.S. state of North Carolina | |

North Carolina's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 34°16′N 78°38′W / 34.26°N 78.64°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1808 |

| Named for | Christopher Columbus |

| Seat | Whiteville |

| Largest community | Whiteville |

| Area | |

| • Total | 955.00 sq mi (2,473.4 km2) |

| • Land | 938.12 sq mi (2,429.7 km2) |

| • Water | 16.88 sq mi (43.7 km2) 1.77% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 50,623 |

| • Estimate (2023) | 50,121 |

| • Density | 53.96/sq mi (20.83/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 7th |

| Website | www |

Columbus County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina, on its southeastern border. Its county seat is Whiteville.[1] As of the 2020 census, the population is 50,623.[2] The 2020 census showed a loss of 12.9% of the population from that of 2010. This included an inmate prison population of approximately 2,500.[3]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The area comprising Columbus County was originally inhabited by the Waccamaw people. Historically, the "eastern Siouans" had territories extending through the area of Columbus County prior to any European exploration or settlement in the 16th century.

English colonial settlement in what was known as Carolina did not increase until the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Following epidemics of new infectious diseases, to which indigenous peoples were exposed in trading and other contact, the Waccamaw and other Native Americans often suffered disruption and fatalities when caught between larger tribes and colonists in the Tuscarora and Yamasee wars. Afterward most of the Tuscarora people migrated north, joining other Iroquoian-speaking peoples of the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy in New York State by 1722. At that point the leaders declared their migration ended and the tribe officially relocated to that area.

The Waccamaw Siouan ancestors retreated for safety to an area of Green Swamp near Lake Waccamaw.[4] Throughout the 19th century, the Waccamaw Siouan were seldom mentioned in the historical record. If descendants intermarried with whites and/or African Americans, their children were assumed to lose their Indian status, although they were often reared in Indian culture. Since North Carolina was a slave society, whites classified anyone with visible African features as slaves and blacks first.

Colonial settlement

[edit]As America was colonized by the British, the area encompassing Columbus County was first organized part of the Bath Precinct of North Carolina, established by the British Crown in 1696. In 1729 a southern portion was split off by the General Assembly to create New Hanover County, and five years later Bladen was formed out of part of New Hanover. In 1764 Brunswick County was formed out of Bladen and New Hanover. Throughout this time the area was largely forested and had few white settlers, though the General Assembly established two roads through the area in 1764. William Bartram, a botanist from Pennsylvania, journeyed to Lake Waccamaw to study the flora and fauna of the region in the 1730s, creating the first detailed written account of the area.[5] At least two skirmishes of the American Revolutionary War were fought on Columbus soil: one near Pireway and another at Brown Marsh.[6]

Creation

[edit]Columbus County was created by the General Assembly on December 15, 1808, to make it easier for local residents to conduct official business without having to travel to the seat of Brunswick County.[6] Columbus was formed from parts of Bladen and Brunswick counties and named in honor of Christopher Columbus.[7] The county's borders were modified several times by legislative act between 1809 and 1821.[8] In 1810, a community was platted on land owned by James B. White for the purpose of creating a county seat.[7] It was originally known as White's Crossing before being incorporated as Whiteville in 1832.[9] The first courthouse and jail, made of wood, were built there in 1809.[6]

Development

[edit]

At the time of its creation, Columbus County was sparsely populated.[10] A new brick courthouse and jail were erected in 1852.[6] The construction of a railroad along the Bladen-Columbus border in the 1860s spurred growth. The laying of the Wilmington, Columbia and Augusta Railroad later in the decade connected Whiteville with Wilmington and supported the development of strong lumber and naval stores industries.[10] The county also produced corn, wheat, cotton, and wool.[11]

Most white men in the county fought during the American Civil War, while most free blacks and mulattoes were exempted from service. The county was spared direct fighting, but the war demands stressed the local labor and food markets, and severe rains in 1863 diminished grain yields. Most residents resorted to trade via the barter system. After Wilmington fell to Union troops in February 1865, Union marauders sacked Whiteville.[12] After the war Columbus' economy grew more heavily reliant on corn and cotton production.[11] In 1877, part of Brunswick County was annexed to Columbus.[13]

In the post-Reconstruction period, after white Democrats regained dominance in politics, they emphasized white supremacy and classified all non-whites as black. For instance, Native Americans could not attend schools for white children. Toward the end of the century, the U.S. Census recorded common Waccamaw surnames among individuals in the small isolated communities of this area.[14]

Tobacco was introduced as a crop in Columbus in 1896, and that year a tobacco warehouse was established in Fair Bluff. It remained a marginal crop until 1914, and at the conclusion of World War I overtook cotton as the county's major cash crop.[15] The county's first bank was opened in 1903.[16] Strawberries were introduced at Chadbourn in 1895, and by 1907 Chadbourn had become one of the leading strawberry producers in the world.[17] Another courthouse and jail were built in 1914.[6]

Ku Klux Klan

[edit]In 1950 Thomas Hamilton, a South Carolina leader of a white supremacist Ku Klux Klan chapter, began a recruiting campaign to expand his organization's reach into Columbus County, focusing on the towns of Chadbourn, Fair Bluff, Tabor City, and Whiteville.[18] In late July they paraded through Tabor City, passing out handbills which exhorted white men to join them in resisting "Jews, nigger, and integrationist quacks".[19] W. Horace Carter, the publisher of the Tabor City Tribune, issued an editorial the following day denouncing the Klan as a violent group and urging local residents to ignore them, leading to a threatening note being placed on his car the following day.[20] The county hosted many Klan sympathizers and a Klavern was organized later that year in Whiteville.[18] The News Reporter of Whiteville, led by editor Willard Cole, joined the Tabor City Tribune in reporting on Klan activities and denouncing the organization, leading to threats against Cole.[21]

The following January the Klansmen began night raids on homes, abducting and flogging residents who they felt had violated traditional mores.[18][20] Over the following months the Klan continued to conduct raids, heightening local tensions.[22] In early October 1951 Klansmen from Fair Bluff abducted a couple and transported them into South Carolina.[18] Abduction crossing state lines was a federal crime, and as a result the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) became involved.[23] In February 1952 the FBI, state agents, and county sheriff's deputies initiated a crackdown and arrested 11 Klansmen responsible for the October abduction.[18] Law enforcement made additional arrests over subsequent months. Of the near 100 Klansmen arrested, 63 including Hamilton were convicted of various crimes.[23] For their efforts against the Klan, in 1953 the Tabor City Tribune and The News Reporter won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service.[24]

Colcor

[edit]By the early 1980s, Columbus County had a reputation for intense political competition marked by accusations of fraud and impropriety.[25][26] The FBI had received several complaints from local police officers and residents about alleged protection rackets run by public officials and election fraud. In early 1980 a former FBI informant moved to the county and reported that he was being told to pay bribes to ensure the smooth operation of his business.[27] Taking into account the previous complains they had received, upon being informed the FBI initiated an undercover investigation into corruption in Columbus County, codenamed "Colcor".[27][28]

FBI agents posed as corrupt businessmen with connections to the Detroit Mafia. They set up an illegal gambling club in Lake Waccamaw to make connections with locals[28] and paid bribes to a local judge and the town's police chief to protect their operation.[27] The agents also paid bribes to county commission chairman Ed Walton Williamson in exchange for political influence.[28] With Williamson's help, the agents devised a scheme to investigate election fraud by instigating a referendum in the town of Bolton to legalize liquor-by-the-drink and supplying a local political leader with funds to buy votes to achieve their desired outcome,[29][30] the first time the FBI had ever tried to manipulate a public election.[28][30] The town ultimately voted in favor of legalizing liquor-by-the-drink.[30] The agents were also asked by State Representative G. Ronald Taylor to burn down a business competitor's property, though Taylor eventually enlisted other men to commit the arson.[28]

The FBI publicly revealed the Colcor operation on July 29, 1982.[31][30] A total of 40 people were indicted for crimes observed during the course of the investigation. Of those indicted, 38 were convicted of crimes, with many reaching plea bargains with prosecutors.[31] The U.S. House of Representatives and the North Carolina State Board of Elections were critical of the FBI's involvement in the vote-buying sting surrounding the liquor referendum in Bolton, with the Board of Elections ultimately nullifying the referendum.[32]

Economic stagnation

[edit]The manufacturing sector in Columbus County began a decline in the 1990s. Between 1999 and 2014, the county lost about 2,000 manufacturing jobs. The number of local farmers also declined.[33] The county was heavily impacted by Hurricane Florence in 2018.[34]

Geography

[edit]Columbus County is bordered by Bladen County, Pender County, Brunswick County, and Robeson County in North Carolina and Horry County and Dillon County in South Carolina. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total land area of 955.00 square miles (2,473.4 km2), of which 938.12 square miles (2,429.7 km2) is land and 16.88 square miles (43.7 km2) (1.77%) is water.[35] It is the third-largest county in North Carolina by land area.[36] Columbus is drained by the Lumber River and Waccamaw River.[37] There are several large lakes within the county, including Lake Tabor and Lake Waccamaw.

One of the most significant geographic features is the Green Swamp, a 15,907-acre area in the north-eastern portion of the county. Highway 211 passes alongside it. The swamp contains several unique and endangered species, such as the venus flytrap. The area contains the Brown Marsh Swamp, and has a remnant of the giant longleaf pine forest that once stretched across the Southeast from Virginia to Texas.[38]

State and local protected areas

[edit]- Columbus County Game Land (part)[39]

- Green Swamp Preserve (part)

- Honey Hill Hunting Preserve

- Juniper Creek Game Land (part)[39]

- Lake Waccamaw State Park

- Lumber River State Park (part)

- North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences at Whiteville

Major water bodies

[edit]Demographics

[edit]2020 census

[edit]As of the 2020 census, there were 50,623 people residing in the county.[36] Unlike the 2010 census figures, the population of incarcerated persons were included in the 2020 figures. In proportions, the county was racially/ethnically 59.3 percent white, 28.6 percent black, 5.8 percent Hispanic, 3.4 percent American Indian, 0.3 percent Asian, 0.2 percent Pacific Islander, 3 percent two or more races, and 0.3 percent other. Compared to state averages, the county reported higher proportions of black and American Indian residents and lower proportions of white, Asian, and Hispanic residents.[40] Whiteville is the largest municipality.[41]

Demographic change

[edit]| Historical population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Between 2010 and 2020, Columbus County lost 7,475 residents, a population decline of 12.9 percent. The U.S. Census Bureau recorded declines in 12 of 14 reported communities.[40] Census experts anticipate a further population decline between 2020 and 2030.[47]

Government and politics

[edit]Government

[edit]Columbus County is governed by a seven-member Board of Commissioners.[48] The county is represented in the North Carolina Senate in district 8 and in the North Carolina House of Representatives in district 46.[49] The county is a member of the regional Cape Fear Council of Governments, where it participates in area planning on a variety of issues.[50]

Judicial system and law enforcement

[edit]Columbus County lies within the bounds of North Carolina's 15th Prosecutorial District, the 13A Superior Court District, and the 13th District Court District.[51] The Columbus County Sheriff's Office provides law enforcement services for the county as well as operating the Columbus County Detention Center.[52] There are two state prisons in the county, one at Tabor City, the Tabor City Correctional Institution, and one at Brunswick.[53]

In 2022 Sheriff Jody Greene was re-elected to office after resigning a couple weeks prior due to allegations of obstructing justice and racism.[54] District Attorney Jon David plans to file a new petition for his removal from office. Currently an investigation regarding him and The Columbus County Sheriff Office's actions is being carried out by North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation.[55] He would late resign from office for the second time in January 2023.[56]

Politics

[edit]| Historical presidential election returns | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After the Reconstruction era, Columbus County's politics fell under the domination of the Democratic Party. Through much of the 20th century, local primaries were the preeminent political contests, marked by intense intraparty competition. General elections often displayed low turnout.[25] Throughout much of the 2000s, the county electorate regularly supported Republican presidential candidates and Democratic local and state candidates. Following the election of Democrat Barack Obama as U.S. president in 2008, Republicans' performance in local races markedly improved.[48] As of 2022, the county hosts about 36,200 registered voters, comprising about 15,344 registered Democrats, 10,100 registered Republicans and 10,700 unaffiliated.[49] Despite Democrats' registration advantage, only one unopposed Democrat was elected to a county office in the 2022 local general elections.[58] In 2024, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump won the county with 67 percent of its vote.[59]

Economy

[edit]The economy of Columbus County centers on agriculture and manufacturing. Columbus farmers produce crops such as pecans and peanuts, along with soybeans, potatoes, and corn. Cattle, poultry, and catfish are other agricultural products in the county. Factories in the region produce textiles, tools, and plywood. Household products such as doors, furniture, and windows are also manufactured in Columbus.[60] The county hosts two industrial parks and shares a third with Brunswick County.[61] International Paper is the largest employer.[62] According to census figures, over 14,000 Columbus residents commute to other counties for work, while about 7,600 residents work within the county.[63] The North Carolina Department of Commerce classifies the county as economically distressed[64] and it has regularly suffered from a higher unemployment rate than the state average.[63]

Transportation

[edit]Airplane facilities are provided by the Columbus County Municipal Airport in Whiteville.[65] The R.J. Corman Railroad Group operates a shortline railroad in the county.[66]

Major highways

[edit]

Future I-74

Future I-74 US 74

US 74

US 74 Bus.

US 74 Bus. US 76

US 76 US 701

US 701

US 701 Bus. (Clarkton)

US 701 Bus. (Clarkton)

US 701 Bus. (Tabor City)

US 701 Bus. (Tabor City)

US 701 Bus. (Whiteville)

US 701 Bus. (Whiteville) NC 11

NC 11 NC 87

NC 87 NC 130

NC 130 NC 131

NC 131 NC 211

NC 211 NC 214

NC 214 NC 242

NC 242 NC 410

NC 410 NC 904

NC 904 NC 905

NC 905

Education

[edit]Columbus is one of the few counties in North Carolina that has two public school systems: one for the county, which mostly serves rural areas, and one for the city of Whiteville. Both are led by elected school boards.[58] The county government maintains a system of six libraries.[67] The county also hosts Southeastern Community College.[68] According to the 2021 American Community Survey, an estimated 14.1 percent of county residents have attained a bachelor's degree or higher level of education.[36]

Healthcare

[edit]Columbus County is served by a single hospital, Columbus Regional Healthcare System, based in Whiteville.[69] According to the 2022 County Health Rankings produced by the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, Columbus County ranked 91st in health outcomes of North Carolina's 100 counties, an improvement over recent years, as it was ranked last from 2010 to 2015. Per the ranking, 26 percent of adults say they are in poor or fair health, the average life expectancy is 74 years, and 17 percent of people under the age of 65 lack health insurance.[70] Columbus County has been heavily impacted by the opioid epidemic[71] and led the state in opioid pills per person from 2006 to 2012 averaging 113.5 pills per person per year.[72]

Communities

[edit]

Cities

[edit]- Whiteville (named county seat in 1832 and the largest community)[73]

Towns

[edit]- Boardman

- Bolton

- Brunswick

- Cerro Gordo

- Chadbourn

- Fair Bluff

- Lake Waccamaw

- Sandyfield

- Tabor City (Incorporated as a town 1904)

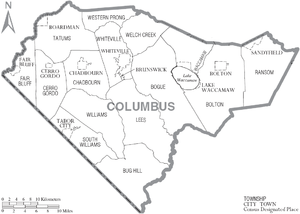

Townships

[edit]- Bogue

- Bolton

- Bug Hill

- Cerro Gordo

- Chadbourn

- Fair Bluff

- Lees

- Ransom

- South Williams

- Tatums

- Waccamaw

- Welch Creek

- Western Prong

- Williams

- Whiteville

Census-designated places

[edit]Unincorporated communities

[edit]- Acme

- Cherry Grove

- Evergreen

- Nakina

- Olyphic

- Pireway

- Riverview

- Sellerstown

- Williamson's Crossroads

See also

[edit]- List of counties in North Carolina

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Columbus County, North Carolina

- Waccamaw Siouan Indians, state-recognized tribe that resides in the county

References

[edit]- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c "QuickFacts: Columbus County, North Carolina". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ "Columbus leaders react to disappointing census results". The News Reporter. August 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ William S. Powell, Encyclopedia of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 1170.

- ^ Rogers 1946, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e Rogers 1946, p. 13.

- ^ a b Corbitt 2000, p. 71.

- ^ Corbitt 2000, p. 72.

- ^ Powell 1976, p. 532.

- ^ a b Justesen 2012, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b Spruill 1990, p. 1.

- ^ Justesen 2012, p. 12.

- ^ Corbitt 2000, p. 73.

- ^ Powell, Encyclopedia of North Carolina, 1170.

- ^ Rogers 1946, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Rogers 1946, p. 14.

- ^ Rogers 1946, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e "Thomas Lemuel Hamilton and the Ku Klux Klan". The Carter-Klan Documentary Project. Center for the Study of the American South. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ Cunningham 2013, p. 28.

- ^ a b Cunningham 2013, p. 29.

- ^ Harris 2015, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Cunningham 2013, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Cunningham 2013, p. 30.

- ^ Harris 2015, p. 220.

- ^ a b White, Katherine; Allen, Ken (August 17, 1982). "Politically, Columbus Is A County With A Past". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 1A, 3A.

- ^ Gilkeson, Bill (August 15, 1982). "FBI Probe: Corrupt Label Produces Ire In Residents Of Columbus". Durham Morning Herald. pp. 1A–2A.

- ^ a b c Alston, Chuck; Swofford, Stan (1984). "Early Recruits Blaze A Trail of Deceit". Greensboro Daily News. The Colcor Chronicles.

- ^ a b c d e McAdams, Ann (February 24, 2021). "Crimes of the Cape Fear: FBI 'Colcor' sting uncovered hotbed of corruption in Southeastern North Carolina". WECT6 News. Gray Media Group. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ Alston, Chuck; Swofford, Stan (January 23, 1984). "The FBI Snares A Patsy: Official Played Role Agents Wrote For Him". Greensboro Daily News. The Colcor Chronicles.

- ^ a b c d Alston, Chuck; Swofford, Stan (January 25, 1984). "FBI Springs Its Last Traps: Agents Fake Arrests To Keep Deception Alive". Greensboro Daily News. The Colcor Chronicles.

- ^ a b Alston, Chuck; Swofford, Stan (January 26, 1984). "Cops As Crooks—Is Justice Served By Deceptions?". Greensboro Daily News. The Colcor Chronicles.

- ^ Lawless 2012, Chapter 14: Stings, Scams, Future Trends and Collateral Attacks : Operation "Colcor".

- ^ Voorheis, Mike (November 2, 2014). "Once a place of hope, Chadbourn in poverty's grip after jobs lost". StarNews Online. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Martin, Edward (October 1, 2019). "Columbus County claws its way back from Florence's strike". Business North Carolina. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "2020 County Gazetteer Files – North Carolina". United States Census Bureau. August 23, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Columbus County, North Carolina". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ Spruill 1990, p. 2.

- ^ "Green Swamp Preserve". The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ a b "NCWRC Game Lands". www.ncpaws.org. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ a b Schofield, Ivey (August 17, 2021). "Columbus leaders react to disappointing census results". The News Reporter. Archived from the original on January 25, 2023.

- ^ Kanu, Hassan (November 21, 2022). "Will sheriff's re-election after resigning over 'fire black people' remarks spur legal action?". Reuters. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ^ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ^ "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ Schofield, Ivey (October 14, 2022). "As developers move in, Columbus County debates preservation and progress". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Nagem, Sarah (November 3, 2022). "Shift to the GOP clouds local races in this rural NC county – especially for sheriff". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ a b Nagem, Sarah (April 20, 2022). "Columbus County voters will go to the polls in May. Here are some primary races to watch". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ "Home". Cape Fear Council of Governments. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ "Columbus County". North Carolina Judicial Branch. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ CCSO. "Columbus County Sheriff's Office - Dedicated To Serve". Columbus County Sheriff's Office. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

- ^ "North Carolina Division of Prisons". doc.state.nc.us. Archived from the original on March 4, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ McAdams, Ann (September 28, 2022). "Sheriff: "I'm sick of these Black bastards.... Every Black that I know, you need to fire him..."". www.wect.com. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Solon, Zach (November 9, 2022). "District Attorney plans to file new petition to remove Columbus County sheriff-elect". www.wect.com. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ WECT Staff (January 4, 2023). "Columbus County Sheriff resigns for the second time; District Attorney holds news conference on the announcement". www.wect.com. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Schofield, Ivey (November 18, 2022). "Push to elect Black candidates to Columbus County school boards was rejected by voters". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved November 19, 2022.

- ^ Rappaport, Ben (November 6, 2024). "Rural southeastern NC gets more red, even as Democrats win key state races". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ Martin, Jonathan. "Columbus County (1808)". North Carolina History Project. John Locke Foundation. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Schofield, Ivey (June 1, 2021). "Workforce is key to capitalizing on agribusiness and population growth in Columbus". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ "Industry". Columbus County Economic Decision. Retrieved January 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Williams, Joseph (June 15, 2022). "Most county residents work elsewhere, and those who do earn more, data shows". The News Reporter. Archived from the original on January 28, 2023.

- ^ Schofield, Ivey (January 23, 2023). "Major expansion planned for business park in southeastern North Carolina". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- ^ Caldwell, Marion (January 9, 2023). "Cape Fear airports significantly contribute to economy, NCDOT report says". WWAY-TV3. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ "Railroad improvements coming to Columbus". The News Reporter. May 16, 2022. Archived from the original on January 26, 2023.

- ^ "Branch Locations, Contact Information and Hours". Columbus County Public Library System. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ Schofield, Ivey (August 17, 2022). "Rural NC community college graduates first class of psychiatric technicians". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ Nagem, Sarah (November 16, 2022). "How safe are the hospitals in North Carolina's Border Belt? New grades released". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ Nagem, Sarah (May 9, 2022). "The fight for better health (and health care) in rural North Carolina". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ Schofield, Ivey (October 9, 2022). "NC sheriff who made racist remarks has history of controversy. Can he outlast this one?". Border Belt Independent. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ "Columbus led state in opioid pills per person; Unsealed data reveals 'virtual road map to the opioid epidemic'". The News Reporter. July 30, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ "NCDA&CS Veterinary Division Animal Welfare Section Civil Penalties and Other Legal Issues". ncagr.gov. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

Works cited

[edit]- Corbitt, David Leroy (2000). The formation of the North Carolina counties, 1663-1943 (reprint ed.). Raleigh: North Carolina Division of Archives and History. OCLC 46398241.

- Cunningham, David (2013). Klansville, U.S.A: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-era Ku Klux Klan (illustrated, reprint ed.). Oxford University Press USA. ISBN 978-0-19-975202-7.

- Harris, Roy J. Jr. (2015). Pulitzer's Gold: A Century of Public Service Journalism (second ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54056-8.

- Justesen, Benjamin R. (2012). George Henry White: An Even Chance in the Race of Life (reprint ed.). Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-4477-0.

- Lawless, Joseph S. (2012). Prosecutorial Misconduct: Law, Procedure, Forms (fourth ed.). Matthew Bender & Company. ISBN 978-1-4224-2213-7.

- Powell, William S. (1976). The North Carolina Gazetteer: A Dictionary of Tar Heel Places. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1247-1.

- Rogers, James A., ed. (1946). Columbus County, North Carolina 1946. Whiteville: The News Reporter. OCLC 9068697.

- Spruill, Willie E. (1990). Soil Survey of Columbus County, North Carolina. United States Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service.

External links

[edit] Geographic data related to Columbus County, North Carolina at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Columbus County, North Carolina at OpenStreetMap- Official website

- The News Reporter